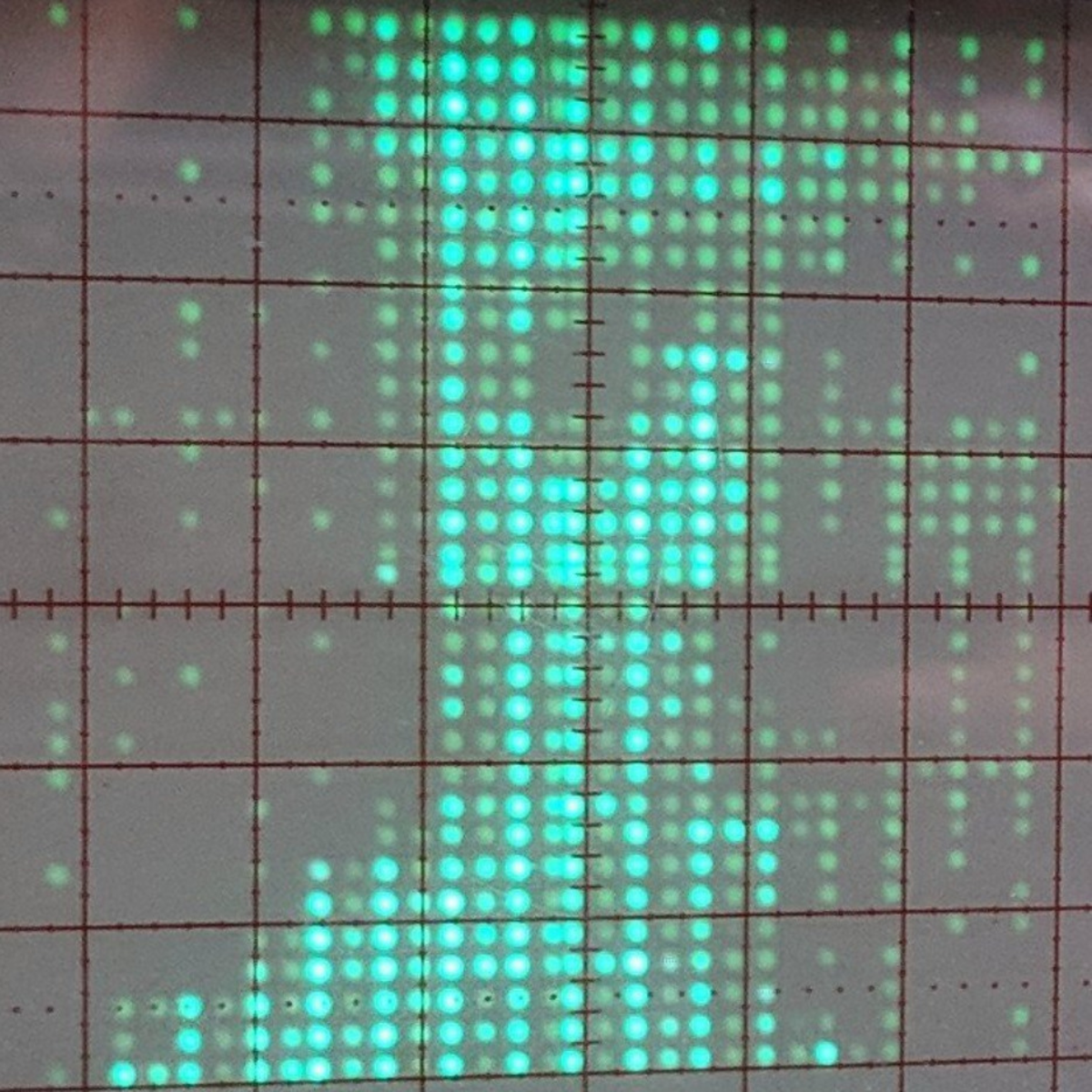

We’re super excited to announce the first round of speakers for Hackaday Berlin! We’re set to convene on Friday night, March 24th for an evening warm up before the main show on Saturday, March 25. Featuring the triumphant return of Voja’s 4-bit badge, a crew of awesome speakers, lightning talks, workshops, music, food, badge hacking, and all the best of the Hackaday community, this will be a day to remember. And then we’ll chill out Sunday morning with a Bring-a-Hack brunch.

So without further ado: the first round of speakers!

Hacking Closed-Source: Reverse Engineering Real-World Products

Closed-source software is prevalent in our everyday lives, limiting our ability to understand how it works, which privacy implication it poses to the processed data, and addressing potential issues in time. Despite the growth of open-source movements, users often have no choice but to rely on closed-source solutions, e.g., for medical devices and IoT products. We’ll discuss key techniques to help you get started with reverse engineering. Hacking your own devices can be challenging, bricking a device is not uncommon, but so is celebrating the moments of a revived and modified device.

Being a Full-Time YouTuber

YouTube is my full-time job and has been for four years. I create STEM education content using everything from 3D printing, CNC, Welding, to Microcontrollers and Coding. Find out how I got started, how I make money, what goes on in the background, and what my future plans are. I’ll tell you how you can do it too!

Hacking your dishwasher for cloudless appliances

Why does your dishwasher, laundry or coffee-pot need to talk to the cloud? In this presentation, Trammell Hudson shows how he reverse engineered the encrypted connections between Home Connect appliances and the Bosch-Siemens Cloud servers, and how you can control your own appliances with your self-hosted MQTT home automation system by extracting the devices’ authentication keys and connecting to their local websocket ports. No cloud required!

Oops, my project ended up in a museum

Parameterized design allows for the adaption of projects to different needs but can also change the aesthetic to a persons liking. Bleeptrack will walk you through the creation process and tools of her generative projects, talk about her experience manufacturing unique pieces and explains how to cope when your freshly finished project gets locked up in an art exhibition for a few months.

Creating Hardware Development Platforms for Real-World Impact: FlowIO Platform

What does it really take do create and deploy a development platform for real-world impact? Why do we need development platforms and how can they democratize emerging fields and accelerate innovation? Why do most platform attempts fail and only very few succeed in terms of impact? I will discuss the key characteristics that any platform technology must have in order for it to be able to useful for diverse users. FlowIO was the winner of the 2021 Hackaday Grand Prize as well as over a dozen other engineering, research, and design awards.

Come join us!