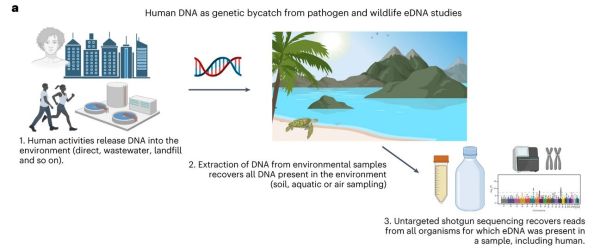

Environmental DNA sampling is nothing new. Rather than having to spot or catch an animal, instead the DNA from the traces they leave can be sampled, giving clues about their genetic diversity, their lineage (e.g. via mitochondrial DNA) and the population’s health. What caught University of Florida (UoF) researchers by surprise while they were using environmental DNA sampling to study endangered sea turtles, was just how much human DNA they found in their samples. This led them to perform a study on the human DNA they sampled in this way, with intriguing implications.

Ever since genetic sequencing became possible there have been many breakthroughs that have made it more precise, cheaper and more versatile. The argument by these UoF researchers in their paper in Nature Ecology & Evolution is that although there is a lot of potential in sampling human environmental DNA (eDNA) to study populations much like is done today already with wastewater sampling, only more universally. This could have great benefits in studying human populations much how we monitor other animal species already using their eDNA and similar materials that are discarded every day as a part of normal biological function. Continue reading “Human DNA Is Everywhere: A Boon For Science, While Terrifying Others”