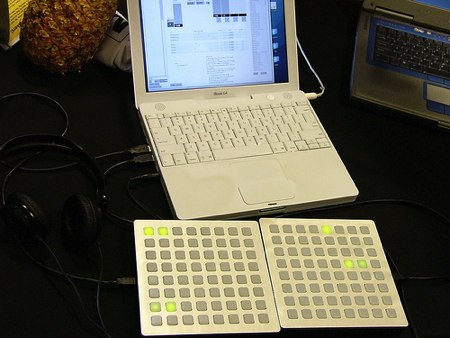

The people from the Monome project are out in full force at the Faire. They’ve got five of the 8×8 pads hooked up for people to play with. The first two pictured above actually work together as a 16 step loop system. There’s also one hooked up as a mixer and another as a drum machine. The fifth one is showing pixelated video from an iSight. The box is really well built. The $500 price point has shocked a lot of people, but it’s really unavoidable since they’re only doing a 200 device run. Something I hadn’t realized before is that the buttons are unique to the device, not off the shelf parts. The button is really a rubber cap that sits over the LED and has a conductive ring at the base. I hope they post a schematic for their 8×8 matrix controller so that anyone could build one. Here are a few more pictures: one, two, three.

Hack Media: Monome

Stop. Watch the video. Monome is an 8×8 grid of backlit buttons for music control. That’s pretty much it. The demo video does an awesome job showing some of the possibilities and I’m sure there will be many interesting developments in the future. I’d love to see what adding a second color for feedback would do.

Will O’Brien from Engadget and I will be attending Make Faire next weekend, where you’ll be able to see and play with the Monome first-hand. We hope to see some of you there.

[via Create Digital Music and Music Thing]

Big Chemistry: Seawater Desalination

For a world covered in oceans, getting a drink of water on Planet Earth can be surprisingly tricky. Fresh water is hard to come by even on our water world, so much so that most sources are better measured in parts per million than percentages; add together every freshwater lake, river, and stream in the world, and you’d be looking at a mere 0.0066% of all the water on Earth.

Of course, what that really says is that our endowment of saltwater is truly staggering. We have over 1.3 billion cubic kilometers of the stuff, most of it easily accessible to the billion or so people who live within 10 kilometers of a coastline. Untreated, though, saltwater isn’t of much direct use to humans, since we, our domestic animals, and pretty much all our crops thirst only for water a hundred times less saline than seawater.

While nature solved the problem of desalination a long time ago, the natural water cycle turns seawater into freshwater at too slow a pace or in the wrong locations for our needs. While there are simple methods for getting the salt out of seawater, such as distillation, processing seawater on a scale that can provide even a medium-sized city with a steady source of potable water is definitely a job for Big Chemistry.

Big Chemistry: Fuel Ethanol

If legend is to be believed, three disparate social forces in early 20th-century America – the temperance movement, the rise of car culture, and the Scots-Irish culture of the South – collided with unexpected results. The temperance movement managed to get Prohibition written into the Constitution, which rankled the rebellious spirit of the descendants of the Scots-Irish who settled the South. In response, some of them took to the backwoods with stills and sacks of corn, creating moonshine by the barrel for personal use and profit. And to avoid the consequences of this, they used their mechanical ingenuity to modify their Fords, Chevrolets, and Dodges to provide the speed needed to outrun the law.

Though that story may be somewhat apocryphal, at least one of those threads is still woven into the American story. The moonshiner’s hotrod morphed into NASCAR, one of the nation’s most-watched spectator sports, and informed much of the car culture of the 20th century in general. Unfortunately, that led in part to our current fossil fuel predicament and its attendant environmental consequences, which are now being addressed by replacing at least some of the gasoline we burn with the same “white lightning” those old moonshiners made. The cost-benefit analysis of ethanol as a fuel is open to debate, as is the wisdom of using food for motor fuel, but one thing’s for sure: turning corn into ethanol in industrially useful quantities isn’t easy, and it requires some Big Chemistry to get it done.

Continue reading “Big Chemistry: Fuel Ethanol”

An Inexpensive Way To Break Down Plastic

Plastic has been a revolutionary material over the past century, with an uncountable number of uses and an incredibly low price to boot. Unfortunately, this low cost has led to its use in many places where other materials might be better suited, and when this huge amount of material breaks down in the environment it can be incredibly persistent and harmful. This has led to many attempts to recycle it, and one of the more promising efforts recently came out of a lab at Northwestern University.

Plastics exist as polymers, long chains of monomers that have been joined together chemically. The holy grail of plastic recycling would be to convert the polymers back to monomers and then use them to re-make the plastics from scratch. This method uses a catalyst to break down polyethylene terephthalate (PET), one of the more common plastics. Once broken down, the PET is exposed to moist air which converts it into its constituent monomers which can then be used to make more PET for other uses.

Of course, the other thing that any “holy grail” of plastic recycling needs is to actually be cheaper and easier than making new plastic from crude oil, and since this method is still confined to the lab it remains to be seen if it will one day achieve this milestone as well. In the meantime, PET can also be recycled fairly easily by anyone who happens to have a 3D printer around.

Biosynthesis Of Polyester Amides In Engineered Escherichia Coli

Polymers are one of the most important elements of modern-day society, particularly in the form of plastics. Unfortunately most common polymers are derived from fossil resources, which not only makes them a finite resource, but is also problematic from a pollution perspective. A potential alternative being researched is that of biopolymers, in particular those produced by microorganisms such as everyone’s favorite bacterium Escherichia coli (E. coli).

These bacteria were the subject of a recent biopolymer study by [Tong Un Chae] et al., as published in Nature Chemical Biology (paywalled, break-down on Arstechnica).

By genetically engineering E. coli bacteria to use one of their survival energy storage pathways instead for synthesizing long chains of polyester amides (PEAs), the researchers were able to make the bacteria create long chains of mostly pure PEA. A complication here is that this modified pathway is not exactly picky about what amino acid monomers to stick onto the chain next, including metabolism products.

Although using genetically engineered bacteria for the synthesis of products on an industrial scale isn’t uncommon (see e.g. the synthesis of insulin), it would seem that biosynthesis of plastics using our prokaryotic friends isn’t quite ready yet to graduate from laboratory experiments.

Plastic On The Mind: Assessing The Risks From Micro- And Nanoplastics

Perhaps one of the clearest indications of the Anthropocene may be the presence of plastic. Starting with the commercialization of Bakelite in 1907 by Leo Baekeland, plastics have taken the world by storm. Courtesy of being easy to mold into any imaginable shape along with a wide range of properties that depend on the exact polymer used, it’s hard to imagine modern-day society without plastics.

Yet as the saying goes, there never is a free lunch. In the case of plastics it would appear that the exact same properties that make them so desirable also risk them becoming a hazard to not just our environment, but also to ourselves. With plastics degrading mostly into ever smaller pieces once released into the environment, they eventually become small enough to hitch a ride from our food into our bloodstream and from there into our organs, including our brain as evidenced by a recent study.

Multiple studies have indicated that this bioaccumulation of plastics might be harmful, raising the question about how to mitigate and prevent both the ingestion of microplastics as well as producing them in the first place.

Continue reading “Plastic On The Mind: Assessing The Risks From Micro- And Nanoplastics”