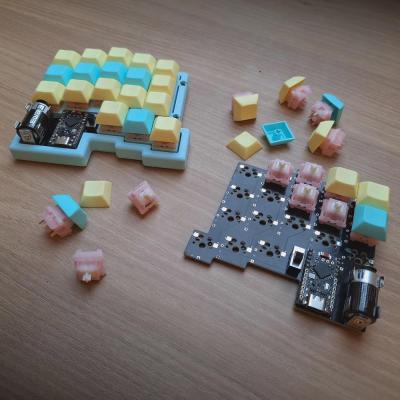

All right, I’ll cut to the chase: Cheap03xD is mainly so cheap because the PCB falls within a 10 x 10 cm footprint. The point was to make a very affordable keyboard — all the parts come to ~40 Euro (~$47). So it would seem that [Lander03xD_] succeeded.

Those are MMD Princess silent switches, which I wouldn’t choose, but [Lander03xD_] is taking this board to the office, so I get it. They sure are a nice shade of pink, anyway, and they go really well with the pastels of the DSA keycaps and the bezel.

One cool thing to note is that the PCBs are reversible, like the ErgoDox. This isn’t [Lander03xD_]’s first board, and it won’t be the last.

Now, let’s talk batteries. [Saixos] pointed out that the design doesn’t appear to include a protection circuit. In case you can’t tell from where you’re sitting, those are nice!nano clones that [Lander03xD_] is using, and they expect a protection circuit.

[Lander03xD_] is going to look through the docs and see what’s what. The goal is not to have any daughter boards, so this may take some rethinking.

Via reddit

Continue reading “Keebin’ With Kristina: The One With The Cheap-O Keyboard”