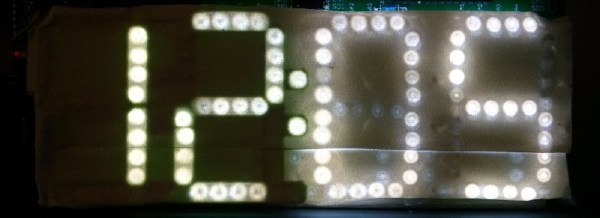

You don’t get much more old school than a sundial, and more new school than 3D printing. So, it is nice to see these two combined in this impressive project: the 3D printed digital sundial. We have seen a few sundial projects before, ranging from LED variants to 3D printed ones, but this one from [Julldozer] takes it to a new level.

In the video, he carefully explains how he designed the sundial. Rather than simply create it as a static 3D model, he used OpenSCAD to build it algorithmically, using the program to create the matrix for each of the numbers he wanted the sundial to show, then to combine these at the appropriate angle into a single, 3D printable model. He has open-sourced the project, releasing the OpenSCAD script for anyone who wants to tinker or build their own. It is an extremely impressive project, and there is more to come: this is the first in a new podcast series called Mojoptix from [Julldozer] that will cover similar projects. We will definitely be keeping an eye on this series.

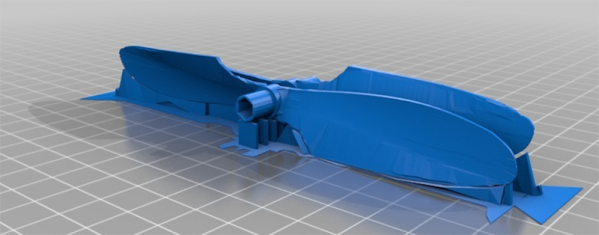

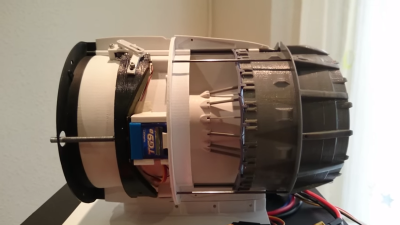

What sets this apart from other jet models is the working reverse thrust system. [Harcoreta] painstakingly modeled the cascade reverse thrust setup on the 787/GEnx-1B combo. He then engineered a way to make it actually work using radio controlled plane components. Two servos drive threaded rods. The rods move the rear engine cowling, exposing the reverse thrust ducts. The servos also drive a complex series of linkages. These linkages actuate cascade vanes which close off the fan exhaust. The air driven by the fan has nowhere to go but out the reverse thrust ducts. [Harcoreta’s] videos do a much better job of explaining how all the parts work together.

What sets this apart from other jet models is the working reverse thrust system. [Harcoreta] painstakingly modeled the cascade reverse thrust setup on the 787/GEnx-1B combo. He then engineered a way to make it actually work using radio controlled plane components. Two servos drive threaded rods. The rods move the rear engine cowling, exposing the reverse thrust ducts. The servos also drive a complex series of linkages. These linkages actuate cascade vanes which close off the fan exhaust. The air driven by the fan has nowhere to go but out the reverse thrust ducts. [Harcoreta’s] videos do a much better job of explaining how all the parts work together.