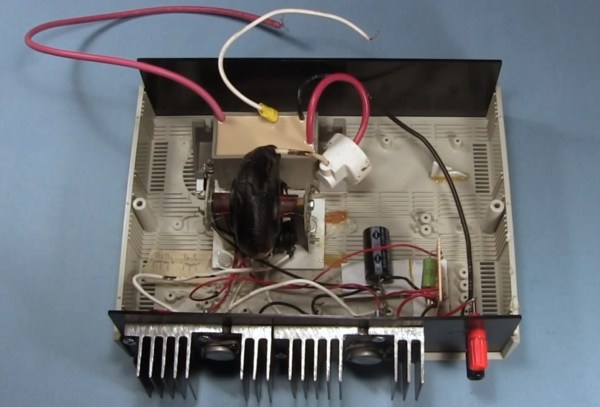

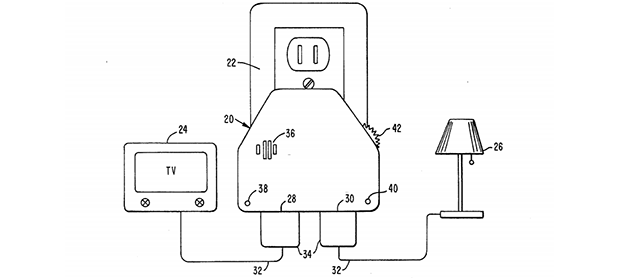

Hackaday readers above a certain age will probably remember the fabulously faddish products developed by Joseph Enterprises. These odd gadgets included the Ove’ Glove, VCR Co-Pilot, the Creosote Sweeping Log, and Chia Pet (Cha-Cha-Cha-Chia) as mainstays of late night commercials, but none were as popular as The Clapper, everyone’s favorite sound-activated switch from the 1980s. [Richard] put up a great virtual teardown of The Clapper, that provides a lot of insight into how this magic relay box actually works, along with some historical context for the world The Clapper was introduced to.

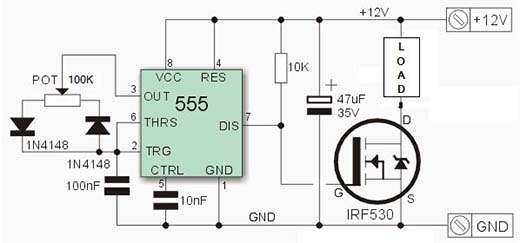

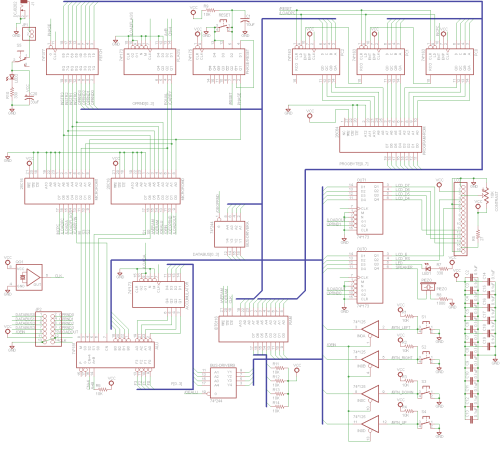

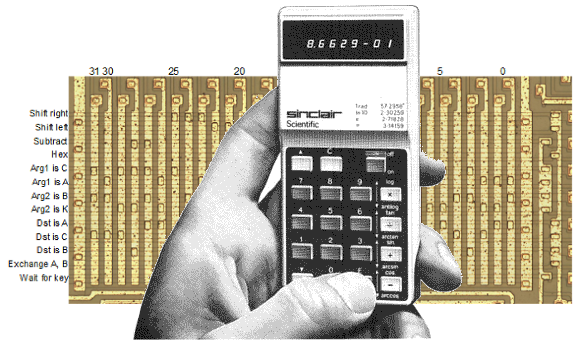

Sound activated switches are nothing new, but the way The Clapper did it was just slightly brilliant. Instead of listening to every sound, the mic inside the magic box sends everything through a series of filters to come up with a very narrow bandpass filter centered around 2500 Hz. This trigger is analyzed by a SGS Thompson ST6210 microcontroller ( 4MHz, ~1kB ROM, 64 bytes of RAM, and 12 I/O pins ) to listen for two repeating triggers within 200 milliseconds. The entire system – including the source code for the MCU – can be seen in the official patent, US5493618.

The Clapper sold many millions of units at a time when a lot of homes were assuredly in a pre-microelectronics world. Yes, in 1986, a lot of TVs had microcontrollers and maybe a washer/dryer combo may have had a few thousand transistors between them. Other than that, The Clapper was many household’s introduction to the ubiquitous computing power we see today, and all with less capability than an Arduino.