For those of us whose interests lie in radio, encountering our first software defined radio must have universally seemed like a miracle. Here is a surprisingly simple device, essentially a clever mixer and a set of analogue-to-digital or digital-to-analogue converters, that can import all the complex and tricky-to-set-up parts of a traditional radio to a computer, in which all signal procession can be done using software.

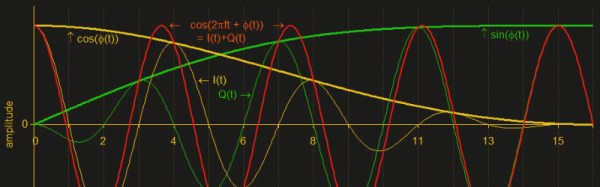

When your curiosity gets the better of you and you start to peer into the workings of a software defined radio though, you encounter something you won’t have seen before in a traditional radio. There are two mixers fed by a two local oscillators on the same frequency but with a 90 degree phase shift, and in a receiver the resulting mixer products are fed into two separate ADCs. You encounter the letters I and Q in relation to these two signal paths, and wonder what on earth all that means.

Continue reading “If The I And Q Of Software Defined Radio Are Your Nemesis, Read On”