The recent trend to smaller and smaller handy talkie (HT) transceivers is approaching the limits of the human interface. Sure, engineers could probably continue shrinking the Baofeng and Wouxun HTs further, but pretty soon they’ll just be too small to operate. And it’s getting to the point where the accessories, particularly the battery charging trays, are getting bulkier than the radios. With that in mind, [Mads Hobye] decided to slim down his backpacking loadout by designing a slimline USB charger for his Baofeng HT.

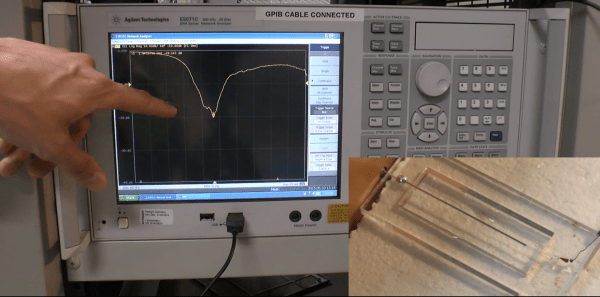

Lacking an external charging jack but sporting a 3.7 volt battery pack with exposed charging terminals on the rear, [Mads] cleverly capitalized on the belt clip to apply spring tension to a laser-cut acrylic plate. A pair of bolts makes contact with the charging terminals on the battery pack, and the attached USB cable allows him to connect to an off-the-shelf 3.7 volt LiPo USB charger, easy to come by in multicopter circles. YMMV – the Baofeng UV-5R dual-band HT sitting on my desk has a 7.4 volt battery pack, so I’d have to make some adjustments. But you have to applaud the simplicity of the build and its packability relative to the OEM charging setup.

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen [Mads] on Hackaday. He and the FabLab RUC crew were recently featured with their open-source robotic arm.

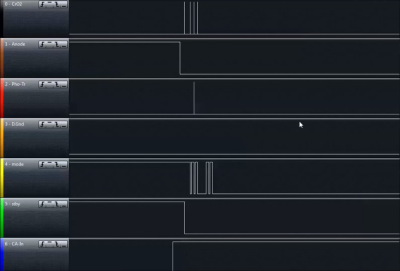

Attacking the outdated Cassette deck [kolonelkadat] knew that inside the maze of gears and leavers, most of it is moving around actuating switches to let the radio know that there is a tape inside and that it can switch to that input and play. Tricking the radio into thinking there is a tape inserted is handled by an Arduino. Using a logic analyzer [kolonelkadat] figured out what logic signals the original unit put out and replicating that in his Arduino code.

Attacking the outdated Cassette deck [kolonelkadat] knew that inside the maze of gears and leavers, most of it is moving around actuating switches to let the radio know that there is a tape inside and that it can switch to that input and play. Tricking the radio into thinking there is a tape inserted is handled by an Arduino. Using a logic analyzer [kolonelkadat] figured out what logic signals the original unit put out and replicating that in his Arduino code.