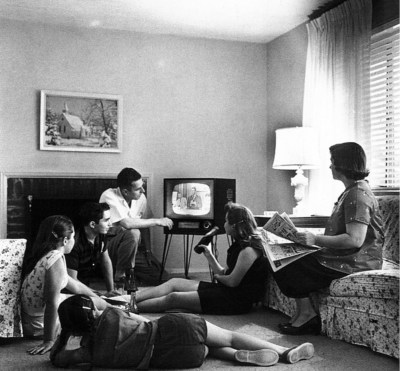

Our smartphones have become our constant companions over the last decade, and it’s often said that they have been such a success because they’ve absorbed the features of so many of the other devices we used to carry. PDA? Check. Pager? Check. Flashlight? Check. Camera? Check. MP3 player? Of course, and the list goes on. But alongside all that portable tech there’s a wider effect on less portable technology, and it’s one that even has a social aspect to it as well. In simple terms, there’s a generational divide that the smartphone has brought into focus, between older people who consume media in ways born in the analogue age, and younger people for whom their media experience is customized and definitely non-linear.

The Kids Just Don’t Listen To The Radio Any More

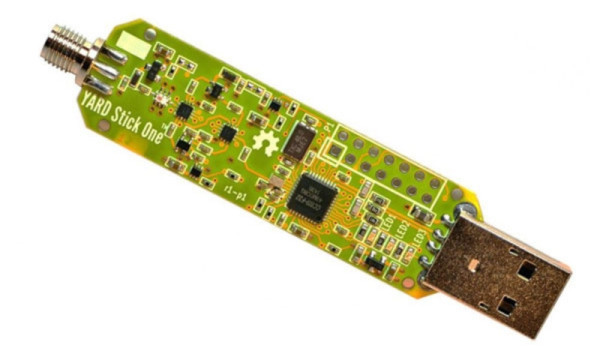

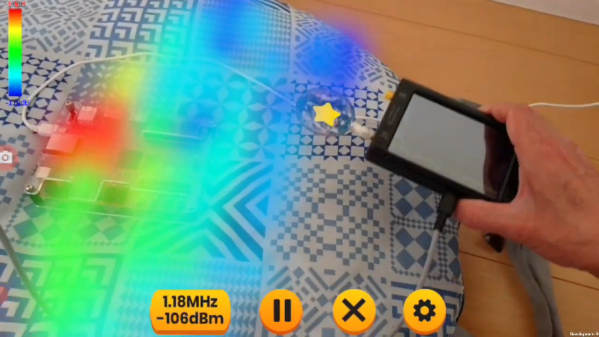

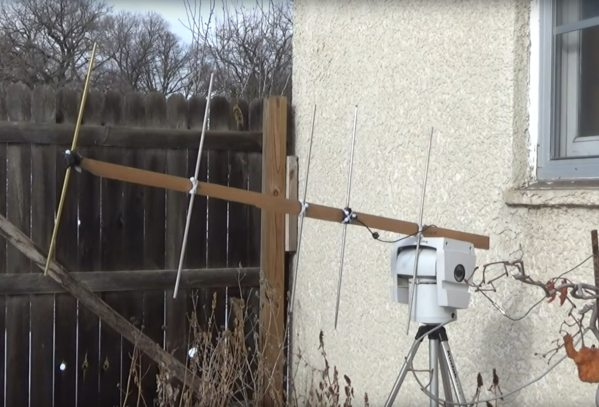

The effect of this has been to see a slow erosion of the once-mighty reach of radio and TV broadcasters, and with that loss of listenership has come less of a need for the older technologies they relied on. Which leaves a fascinating question here at Hackaday, what is going to happen to all that spectrum? Indeed, there’s a deeper question behind all that, is lower frequency spectrum even that valuable any more?

In the old days, we had analogue TV in several-MHz-wide channels spread across a large part of the UHF bands and some smaller chunks of VHF. Among that we had 20 MHz of FM broadcasting around the 100 MHz mark, and disregarding shortwave, then a MHz of AM down around 1 MHz. Europeans got a bonus band down there too: we’ve got Long Wave, over 100 kHz of AM goodness roughly centered around 200 kHz.

Continue reading “What’s Going To Happen To Legacy Broadcast Bands When The Lights Go Out?”