Having grown up with 386-level systems during the early 90s like so many of us, [Alexandru Groza] experienced an intense longing to experience the nostalgia of these computer systems from an interesting angle: by building his own 80386DX-based single board computer. Courtesy of the 16-bit ISA form factor, the entire system fits into a 16-bit ISA backplane which then provides power and expansion slots for further functionality beyond what is integrated on the SBMC card.

Having started the project in 2019, it is now in the home stretch towards completion. Featuring an 80386DX and 80387DX FPU alongside 128 kB of cache and a grand total of 32 MB of RAM, an OPTi chipset was used to connect with the rest of the system alongside the standard 8042-class PS/2 keyboard and mouse controller. A large part of the fun of assembling such a system is that while the parts themselves are easy enough to obtain, finding datasheets is hard to impossible for some components.

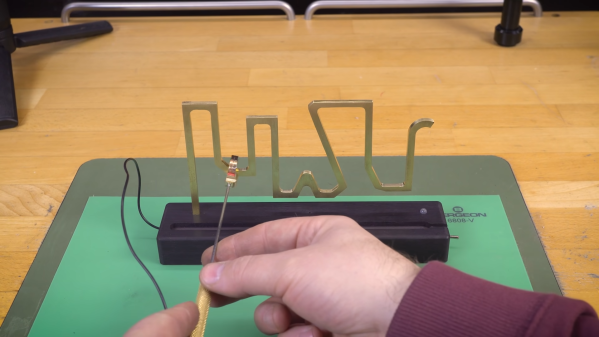

Undeterred, some reverse-engineering of signaling on functional mainboards was sufficient to fill in the missing details. Helpfully, [Alexandru] provides the full schematics and BOM of the resulting board and takes us along with bootstrapping the system after obtaining the PCBs and components. After an initial facepalm moment due to an incorrectly inserted (and subsequently very dead) CPU and boot issues, ultimately [Alexandru] gave up on the v1.6 revision of the board

Fortunately the v1.8 revision with a logic analyzer led to a number of discoveries that has led to the system mostly working, minus what appears to be DMA-related issues. Even so, it is a remarkable achievement that demonstrates the complexity of these old systems.