[Kate Reed] found a quote by a homeless person that said “No one sees us”, which led her to exploring what it actually means to be invisible — and if we actually choose to be invisible by hiding away our emotions, sexual preference, race or income. She realized that too often, we choose to only see what we want to see, rendering all the rest invisible by looking away. Her public art campaign and Hackaday Prize entry “Invisible” aims to increase social awareness and strengthening the community by making hidden thoughts, feelings and needs visible.

The Hackaday Prize1542 Articles

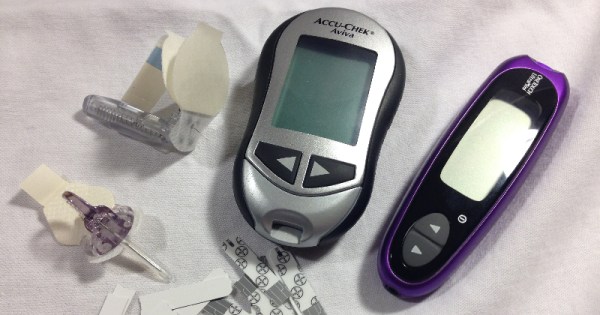

Hackaday Prize Entry: A Universal Glucose Meter

If you need an example of Gillette’s razor blade business plan, don’t look at razors; a five pack of the latest multi-blade, aloe-coated wonder shaver is still only about $20. Look a glucose meters. Glucose meters all do the same thing – test blood glucose levels – but are imminently proprietary, FDA regulated, and subsidized by health insurance. It’s a perfect storm of vendor lock-in that would make King Gillette blush.

For his Hackaday Prize entry, [Tom] is building what was, until now, only a dream. It’s a universal glucometer that uses any test strip. The idea, of course, is to buy the cheapest test strip while giving the one-fingered salute to the companies who release more models of glucometers in a year than Apple does phones.

As with any piece of consumer electronics, there are plenty of application guides published by the biggest semiconductor companies explaining to engineers how to use their part to build a device. After reviewing the literature from TI, Maxim, Freescale, and Microchip, and a few research articles on the same subject, [Tom] has a pretty good idea how to build a glucometer.

The trick now is figuring out how to build an adapter for every make and model of test strip. This is more difficult than it sounds, because some test strips have two contacts, some have three, some have five, and all of them are proprietary. Calibration will be an issue, but if you’re building a glucometer from scratch, that’s not a very big problem.

This is one of the most impressive projects we’ve seen in this year’s Hackaday Prize. No, it shouldn’t be the only way a diabetic tracks their sugar levels, but diabetics shouldn’t rely only on test strips anyway. If you’re looking for a Hackaday Prize project that has the potential to upend an industry, this is the one.

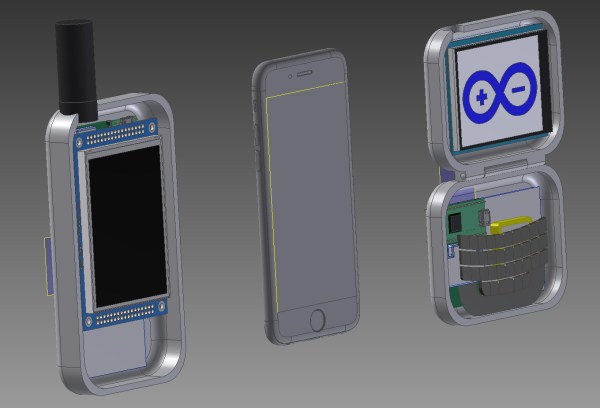

Hackaday Prize Entry: MyComm Handheld Satellite Messenger

We live in a connected world, but that world ends not far beyond the outermost cell phone tower. [John Grant] wants to be connected everywhere, even in regions where no mobile network is available, so he is building a solar powered, handheld satellite messenger: The MyComm – his entry for the Hackaday Prize.

The MyComm is a handheld touch-screen device, much like a smartphone, that connects to the Iridium satellite network to send and receive text messages. At the heart of his build, [John] uses a RockBLOCK Mk2 Iridium SatComm Module hooked up to a Teensy 3.1. The firmware is built upon a FreeRTOS port for proper task management. Project contributor [Jack] crafted an intuitive GUI that includes an on-screen keyboard to write, send and receive messages. A micro SD card stores all messages and contact list entries. Eventually, the system will be equipped with a solar cell, charging regulator and LiPo battery for worldwide, unconditional connectivity.

2016 will be an interesting year for the Iridium network since the first satellites for the improved (and backward-compatible) “Iridium NEXT” network are expected to launch soon. At times the 66 Iridium satellites currently covering the entire globe were considered a $5B heap of space junk due to deficiencies in reliability and security. Yet, it’s still there, with maker-friendly modems being available at $250 and pay-per-use rates of about 7 ct/kB (free downstream for SDR-Hackers). Enjoy the video of [Jack] explaining the MyComm user interface:

Continue reading “Hackaday Prize Entry: MyComm Handheld Satellite Messenger”

The Politest Patent Discussion, OSHW V. Patents

We’ve covered [Vijay] refreshable braille display before. Reader, [zakqwy] pointed us to an interesting event that occured in the discussion of its Hackaday.io project page.

[Vijay] was inspired by the work of [Paul D’souza], who he met at Makerfaire Bangalore. [Paul] came up with a way to make a refreshable braille display using small pager motors. [Vijay] saw the light, and also felt that he could make the vibrating motor display in such a way that anyone could make it for themselves at a low cost.

Of course, [Paul], had patented his work, and in this case rightly so. As jaded as we have become with insane patent trolls, our expectation on receiving the tip was that [Paul] had sued [Vijay] out of house and home and kicked his dog while he was at it. A short google search shows that [Paul] is no patent troll, and is a leader in his field. He has done a lot to help the visually impaired with his research and inventions.

Instead we were greeted by a completely different conversation. [Paul] politely mentioned that his lawyer informed him that in order to protect his IP he needed to let [Vijay] know exactly how the information could be used. No cease and desist, in fact he encouraged [Vijay] to continue his open research as long as he made it clear that the methods described could not be used to make a marketable product without infringing on [Paul]’s patents. They’d need to get in touch with [Paul] and work something out before doing such.

[Vijay] responded very well to this information. His original goal was to produce a cheap braille display that could be made and sold by anyone. However, he did use [Paul]’s work as a basis for his variation. Since [Paul]’s commercial interests relied on his patent, there was a clear conflict, and it became obvious to [Vijay] that if he wanted to meet his goal he’d have to pick a new direction. So, he released his old designs as Creative Commons, since the CERN license he was using was invalidated by [Paul]’s patent. He made it very clear that anyone basing their work off those designs would have to get in touch with [Paul]. Undaunted by this, and still passionate about the project, [Vijay] has decided to start from scratch and see if he can invent an entirely new, unprotected mechanism.

Yes, the patent system is actually encouraging innovation by documenting prior work while protecting commercial and time investments of beneficial inventors. Well. That’s unexpected.

Kudos to [Paul] for encouraging the exploration of home hackers rather than playing the part of the evil patent owner we’ve all come to expect from these stories. Also [Vijay], for acting maturely to [Paul]’s polite request and not ceasing his work.

Hackaday Prize Entry: A Local Positioning System

Use of the global positioning system is all around us. From the satnav in your car to quadcopters hovering above a point, there are hundreds of ways we use the Global Positioning System every day. There are a few drawbacks to GPS: it takes a while to acquire a signal, GPS doesn’t work well indoors, and because nodes on the Internet of Things will be cheap, they probably won’t have a GPS receiver.

These facts open up the door for a new kind of positioning system. A local positioning system that uses hardware devices already have, but is still able to determine a location within a few feet. For his Hackaday Prize entry, [Blecky] is building the SubPos Ranger, a local positioning system based on 802.15.4 radios that still allows a device to determine its own location.

The SubPos Ranger is based on [Blecky]’s entry for the 2015 Hackaday Prize, SubPos that used WiFi, RSSI, and trilateration to determine a receiver’s position in reference to three or more base stations. It works remarkably well, even in places where GPS doesn’t, like parking garages and basements.

The SubPos Ranger is an extension of the WiFi-only SubPos, based on 802.15.4, and offers longer range and lower power than the WiFi-only SubPos system. It’s still capable of determining where a receiver is to within a few feet, making this the ideal solution for devices that need to know where are without relying on GPS.

Hackaday Prize Entry: SunLeaf

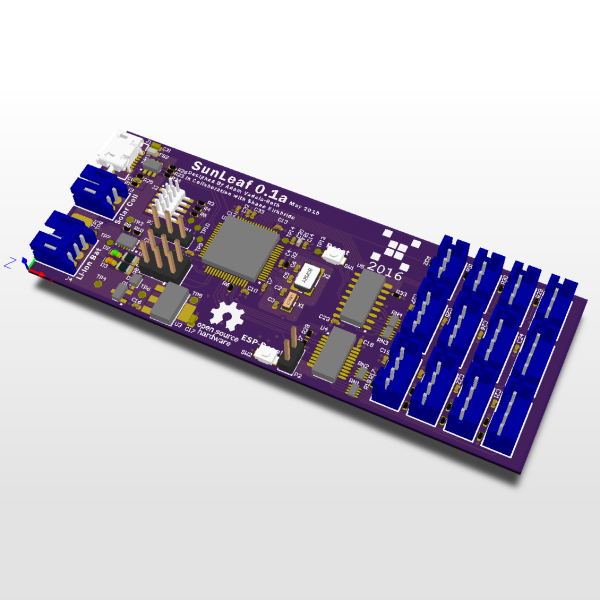

If there’s one place where the Internet of Things makes sense, it’s agriculture. From vast fields of soybeans, corn, and a different variety of corn, to the backyard garden, knowing how much sun, and rain crops get can vastly increase yields. For their Hackaday Prize project, [Adam] and [Shane] are building a board designed explicitly for plants. It’s called the SunLeaf, and it has all the sensors and radios a good remote sensing board needs.

The SunLeaf is built around an ARM Cortex M4 microcontroller with an ESP8266 module for WiFi connectivity. Sensors are important for any remote sensing board, and for this the guys are going with SeeedStudio Grove connectors, providing four UARTs, four I2C, and four analog ports.For remote sensing applications, you generally can’t rely on mains power, so SunLeaf includes a port for a solar panel and a battery charger.

Although this project was originally a redesign of [Adam] and [Shane]’s Hackaday Prize entry from last year, what they’ve come up with is a great device for data logging, autonomous control, and environmental sensing for anything, from farms to weather stations.

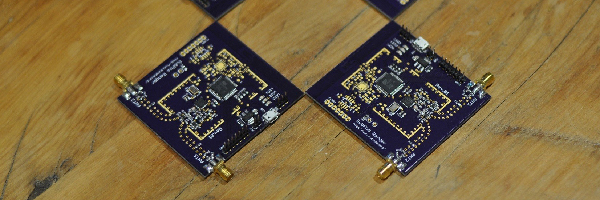

Hackaday Prize Entry: A 400MHz Modem

The Internet of Things has been presented as the future of consumer electronics for the better part of a decade now. Billions have been invested, despite no one actually knowing what the Internet of Things will do. Those billions need to go somewhere, and in the case of Texas Instruments, it’s gone straight into the next generation of microcontrollers with integrated sub-GHz radios. [M.daSilva]’s entry to the 2016 Hackaday Prize turns these small, cheap, radios into a portable communicator.

This ‘modem for the 400 MHz band’ consists simply of an ATmega microcontroller, TI’s CC1101 sub-GHz transceiver, an OLED display, and a UHF power amplifier. As far as radios radios go, this is as bare bones as it gets, but with the addition of a USB to serial chip and a small program this radio can send messages to anyone or anything in range. It’s a DIY pager with a couple chips and some firmware, and already the system works.

[M.daSilva] has two use cases in mind for this device. The first is an amateur radio paging system, where a base station with a big power amp transmits messages to many small modules. The second use is a flexible mdoule that links PCs together, using Ham radio’s data modes. With so many possibilities, this is one of the best radio builds we’ve seen in this year’s Hackaday Prize.