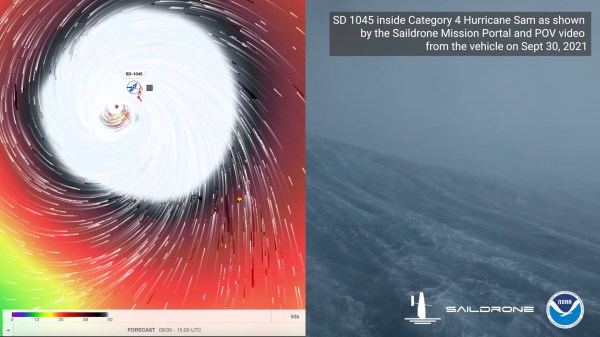

It is unlikely that as a young lad [Richard Jenkins] would had have visions of sailing into the eye of a Category-4 hurricane. Yet that’s exactly what he’s done with the Explorer 1045, an uncrewed sailing vehicle built by his company, Saildrone. If that weren’t enough, footage from the vessel enduring greater than 120 MPH (almost 200 km/h) winds and 50 foot (15 M) waves was posted online the very next day, and you can see it below the break. We’re going to take a quick look at just two of the technologies that made this possible: Advanced sails and satellite communication. Both are visible on Explorer 1045’s sibling 1048 as seen below:

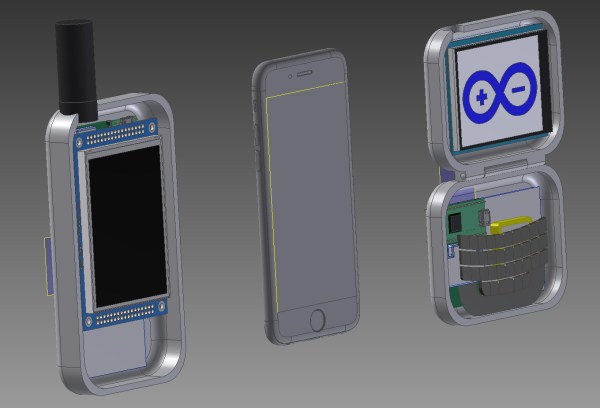

The most prominent feature of course is the lack of a traditional sail. You see, from 1999-2009, [Richard Jenkins] was focused on setting the land world speed record for a wind powered vehicle. He set that record at 126.1 mph by maturing existing sail wing technology. [Richard] did away with conventional rigging and added a boom with a control surface on it, much like the fuselage and empennage of a sailplane.

Instead of adjusting rigging, the control surface could be utilized to fly the wing into its optimal position while using very little energy. [Richard] has been able to apply this technology at his company, Saildrone. The 23 foot Explorer vessel and its big brothers are the result.

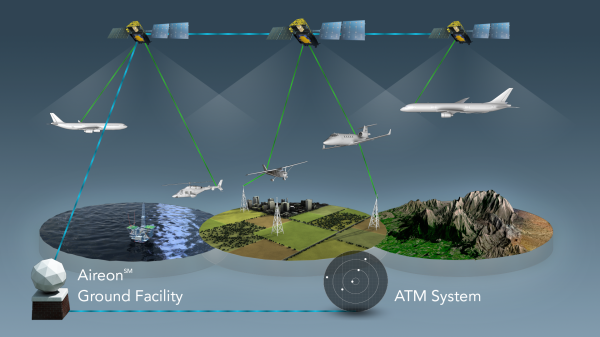

How is it that the world was treated to the view from inside the eye of a hurricane only a day after the video was recorded? If you look at the stern of the vessel, you can see a domed white cylinder. It is a satellite communication base station called the Thales VesseLINK. Thales is one of the partner companies that built the satellites for the Iridium NEXT fleet, which has 66 operational satellites in Low Earth Orbit. The Iridium Certus service uses its L-Band (1.6 GHz) signal to provide up to 352 kbps of upload speed and 704 kbps down. While not blazing fast, the service is available anywhere in the world and is reliable because it is not prone to rain fade and other weather based interference.

With just these two recent innovations, the Explorer 1045 was able to sail to the eye of a hurricane, record footage and gather data, and then ship it home just hours later. And we’re hardly exploring the tip of the iceberg. More than just sailboat based cameras, these scientific instruments are designed to survive some of the harshest environments on the planet for over a year at a time. They are a marvel of applied engineering, and we’re positive that there are some brilliant hacks hiding under that bright orange exterior.

If uncrewed sailing vessels float your boat, you might also enjoy this autonomous solar powered tugboat, or that time a submarine ran out of fuel and sailed home on bed sheets.

Continue reading “How Does A Sail Drone Bring Home Hurricane Footage In Record Time?”