There are lots of ways to move a robot ranging from wheels, treads, legs, and even propellers through air or water. Once you decide on locomotion, you also have to decide on the configuration. One possible way to use wheels is with a swerve drive — a drive with independent motors and steering on each wheel. Prolific designer [LoboCNC] has a new version of his swerve drive on Thingiverse. The interesting thing is that it’s nearly all 3D printed.

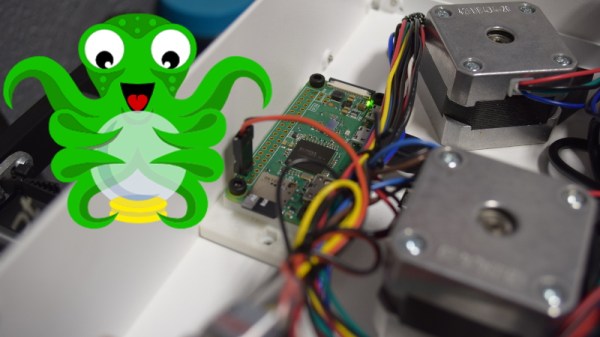

You do need a few metal parts, a belt, two motors, and — no kidding — airsoft BBs, used as bearings. There are 3 parts you have to fabricate, which could take some work on a lathe, so it isn’t completely 3D printed.

[LoboCNC] points out that the assembly is lightweight and is not made for heavy robots. Apparently, though, his idea of lightweight is no more than 20 pounds per wheel, so that’s still pretty large in our book. The two motors allow for one motor to provide drive rotation while the other one — which includes an encoder — to steer. Of course, the software has to account for the effect of steering each wheel separately, but that’s another problem.

This robotic drivetrain is just thing for a car-like robot. If you are a little lonesome you could always print out ASPIR, instead. Or if you want an exotic 3D printed way to move things, you might get some inspiration from Zizzy. If you want a swerve drive that doesn’t require any machining or 3D printing, you might enjoy the video from another FIRST team, below.

Continue reading “Robotic Drive Train Is Nearly All 3D Printed”