The FAA and DOT have finalized their rules for small Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS, or drones), and clarified rules for model aircraft. This is the end of a long process the FAA undertook last year that has included a registry system for model aircraft, and input from members of UAS and model aircraft industry including the Academy of Model Aeronautics and 3D Robotics.

Model Aircraft

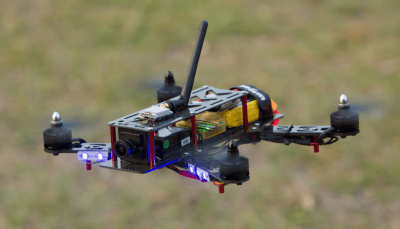

Since the FAA began drafting the rules for unmanned aircraft systems, it has been necessary to point out the distinction between a UAS and a model aircraft. Thanks to the amazing advances in battery, brushless motor, and flight controller technology over the past decade, the line between a drone and a model aircraft has been fuzzed, and onboard video systems and FPV flying have only blurred the distinction.

The distinction between a UAS and model aircraft is an important one. Thanks to the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2012, the FAA, “may not promulgate any rule or regulation regarding a model aircraft” under certain conditions. These conditions include aircraft flown strictly for hobby or recreational use, operated in accordance with a community-based set of safety guidelines (read: the safety guidelines set by the Academy of Model Aeronautics), weighs less than 55 pounds, gives way to manned aircraft, and notifies the operator of an airport when flown within five miles of a control tower.

Despite laws enacted by congress, the FAA saw it necessary to create rules and regulations for model aircraft weighing less than 55 pounds, and operated in accordance with a community-based set of safety guidelines. The FAA’s drone registration system doesn’t make sense, and there is at least one pending court case objecting to these rules.

The FAA’s final rules for UAS, drones, and model airplanes change nothing from the regulations made over the past year. If your drone weighs more than 250 grams, you must register it. For model aircraft, and unmanned aircraft systems conducting ‘hobbyist operations’, nothing has changed.

Unmanned Aerial Systems

The finalized rule introduced today concerns only unmanned aircraft systems weighing less than 55 pounds conducting non-hobbyist operations. The person flying the drone must be at least 16 years old and hold a remote pilot certificate with a small UAS rating. This remote pilot certificate may be obtained by passing an aeronautical knowledge test, or by holding a non-student Part 61 pilot certificate (the kind you would get if you’d like to fly a Cessna on the weekends)

What this means

Under the new regulations, nothing for model aircraft has changed. The guys flying foam board planes will still have to deal with a registration system of questionable legality.

For professional drone pilots – those taking aerial pictures, farmers, or pilots contracting their services out to real estate agents – the situation has vastly improved. A pilot’s license is no longer needed for these operations, and these aircraft may be operated in class G airspace without restriction. Drone use for commercial purposes is now possible without a pilot’s license. This is huge for many industries.

These rules do not cover autonomous flight. This is, by far, the greatest shortcoming of the new regulations. The most interesting applications of drones and unmanned aircraft is autonomous flight. With autonomous drones, farmers could monitor their fields. Amazon could deliver beer to your backyard. There are no regulations regarding autonomous flight from the FAA, and any business plans that hinge on pilot-less aircraft will be unrealized in the near term.

DJI Phantoms are now ‘drones’

This is a quick aside, but I must point out the FAA press release was written by someone with one of two possible attributes. Either the author of this press release paid zero attention to detail, or the FAA has a desire to call all unmanned aircraft systems ‘drones’.

The use of the word ‘drone’ in the model aircraft community has been contentious, with quadcopter enthusiasts making a plain distinction between a DJI Phantom and a Predator drone. Drones, some say, have the negative connotation of firing hellfire missiles into wedding parties and killing American citizens in foreign lands without due process, violating the 5th amendment. Others have classified ‘drones’ as having autonomous capability.

This linguistic puzzle has now been solved by the FAA. In several places in this press release, the FAA equates ‘unmanned aircraft systems’ with drones, and even invents the phrase, ‘unmanned aircraft drone’. Language is not defined by commenters on fringe tech blogs, it is defined by common parlance. Now the definition of ‘drone’ is settled: it is an unmanned, non-autonomous, remote-controlled flying machine not flown for hobby or recreational use.