Some people like to do things the hard way. Maybe they drive a manual transmission, or they bust out the wire wrap tool instead of a soldering iron, or they code in assembly to stay close to the machine. Doing things the hard way certainly has its merits, and we are not here to argue about that. Scott Shawcroft — project lead for CircuitPython — on the other hand, makes a great case for doing things the easy way in his talk at the 2019 Hackaday Superconference.

In fact, he proved how easy it is right off the bat. There he stood at the podium, presenting in front of a room full of people, poised at an unfamiliar laptop with only the stock text editor. Yet with a single keystroke and a file save operation, Scott was able make the LEDs on his Adafruit Edge Badge — one of the other pieces of hackable hardware in the Supercon swag bag — go from off to battery-draining bright.

Code + Community

As Scott explains, CircuitPython prides itself on being equal parts code and community. In other words, it’s friendly and inviting all the way around. Developing in CircuitPython is easy because the entire environment — the code, toolchain, and the devices — are all extremely portable. Interacting with sensors and other doodads is easy because of the import and library mechanics Python is known for, both of which are growing within the CircuitPython ecosystem all the time.

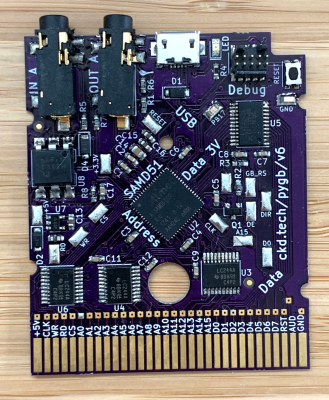

CircuitPython is so friendly that it can even talk to old hardware relatively easily without devolving into a generational battle. To demonstrate this point, Scott whipped out an original Nintendo Game Boy and a custom cartridge, which he can use to play fun sounds via the Game Boy’s CPU.

Now You’re Playing With Python

Now You’re Playing With Python

It’s interesting to see the platforms on which Scott has used the power of CircuitPython. The Game Boy brings the hardware for sound and pixel generation along with some logic, but he says it’s the code on the cartridge that does the interesting stuff.

The CPU communicates with carts at a rate of 1MHz. As long as you can keep this rate up and the CPU understands your instructions, you can get it to do anything you want.

Scott’s custom cart has a 120MHz SAMD51. He spends a second explaining how he gets from Python libraries down to the wire that goes to the Game Boy’s brain — basically, the C code underneath CircuitPython accesses direct structs defined within the SAMD to do Direct Memory Access (DMA), which allows for jitter-free communication at 1MHz.

He’s using the chip’s lookup tables to generate a 1MHz signal out of clock, read, and A15 in order to send music-playing instructions to the sound register of the Game Boy’s CPU. It sounds like a lot of work, but CircuitPython helps to smooth over the dirty details, leaving behind a simpler interface.

If you want easy access to hardware no matter how new or nostalgic, the message is clear: snake your way in there with CircuitPython.

Continue reading “Scott Shawcroft Is Programming Game Boys With CircuitPython”