We have all been stuck inside for too long, and maybe that’s why we have recently seen a number of projects attempting to help humans take better care of their housemates from Kingdom Plantae. To survive, plants need nutrients, light, and water. That last one seems tricky to get right; not too dry and not drowning them either, so [rbaron’s] green solder-masked w-parasite wireless soil monitor turns this responsibility over to your existing home automation system.

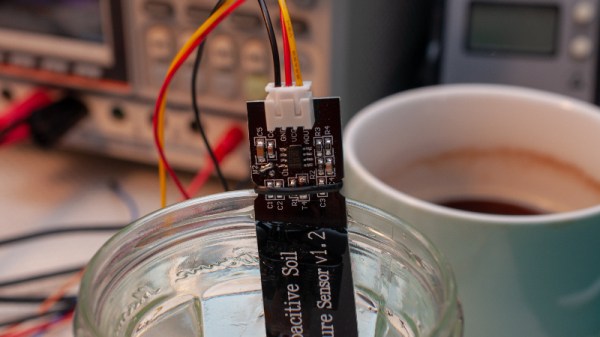

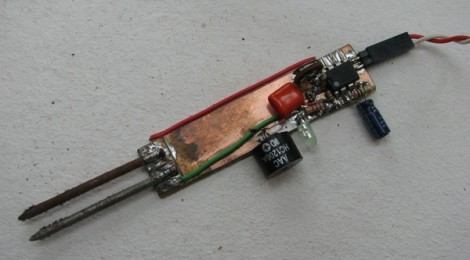

Like this low-power soil sensor project and the custom controller for six soil sensors, [rbaron’s] w-parasite uses a “parasitic capacitive” moisture sensor to determine if it’s time to water plants. This means that unlike resistive soil moisture sensors, here the copper traces are protected from corrosion by the solder mask. For those wondering how they work, [rbaron]’s Twitter thread has a great explanation.

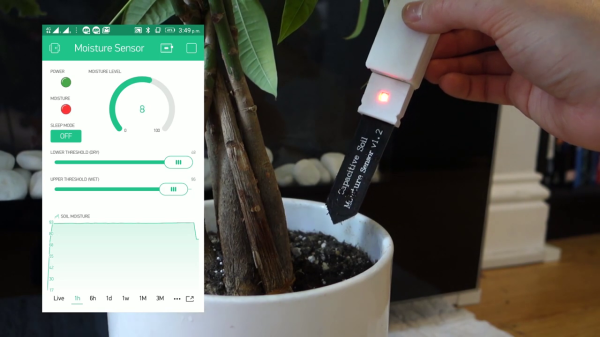

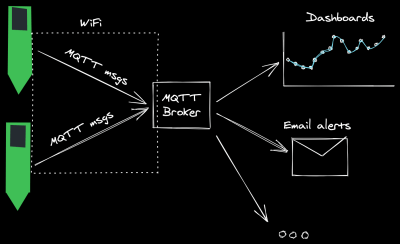

The “w” in the name is for WiFi as the built-in ESP-32 module then takes the moisture reading and sends an update wirelessly via MQTT. Depending on the IQ of your smart-home setup, you could log the data, route an alert to a cellphone, light up a smart-bulb, or even switch on an irrigation system.

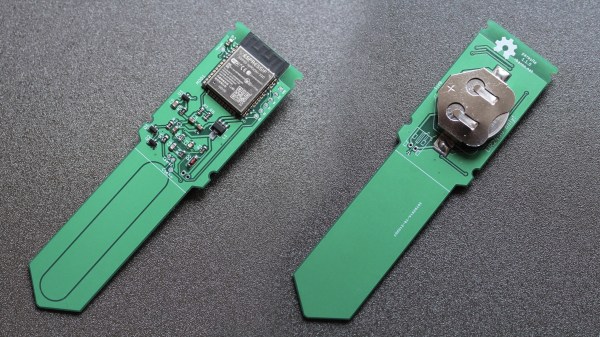

[rbaron] has shared a string of wireless hacks, controlling the A/C over Slack and a BLE Fitness Tracker that inspired more soldering than jogging. We like how streamlined this solution is, with the sensor, ESP-32 module, and battery all in a compact single board design. Are you asking yourself, “but how is a power-hungry ESP-32 going to last longer than it takes for my geraniums to dry out?” [rbaron] is using deep sleep that only consumes 15uA between very quick 500ms check-ins. The rechargeable LIR2450 Li-Ion coin cell shown here can transmit a reading every half hour for 90 days. If you need something that lasts longer than that, use [rbaron]’s handy spreadsheet to choose larger batteries that last a whole year. Though, let’s hope we don’t have to spend another whole year inside with our plant friends.

[rbaron] has shared a string of wireless hacks, controlling the A/C over Slack and a BLE Fitness Tracker that inspired more soldering than jogging. We like how streamlined this solution is, with the sensor, ESP-32 module, and battery all in a compact single board design. Are you asking yourself, “but how is a power-hungry ESP-32 going to last longer than it takes for my geraniums to dry out?” [rbaron] is using deep sleep that only consumes 15uA between very quick 500ms check-ins. The rechargeable LIR2450 Li-Ion coin cell shown here can transmit a reading every half hour for 90 days. If you need something that lasts longer than that, use [rbaron]’s handy spreadsheet to choose larger batteries that last a whole year. Though, let’s hope we don’t have to spend another whole year inside with our plant friends.

We may never know why the weeds in the cracks of city streets do better than our houseplants, but hopefully, we can keep our green roommates alive (slightly longer) with a little digital nudge.