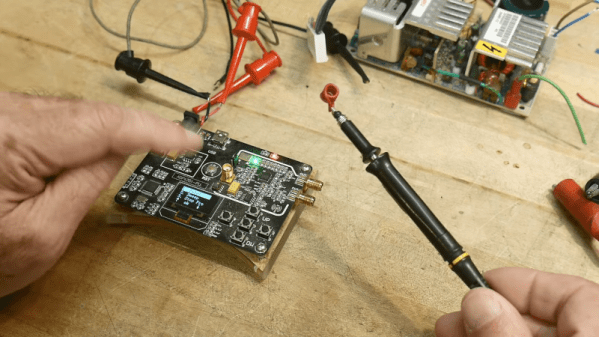

If you want to measure AC or DC current with an oscilloscope, a current clamp is a great way to do it. The clamp surrounds the wire, so you don’t need to break the connection to take your measurements. These used to be expensive, although we’ve seen some under $100, if you shop. We don’t know if it was cost or principle that motivated [Electronoobs] to build his own current clamp, but he did.

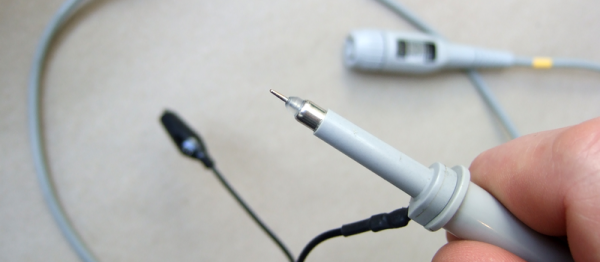

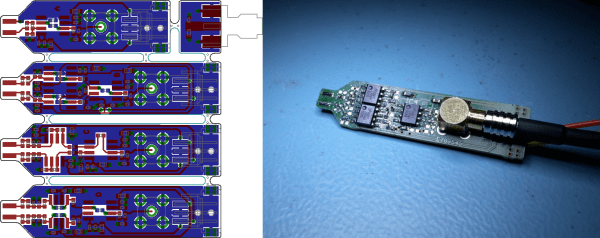

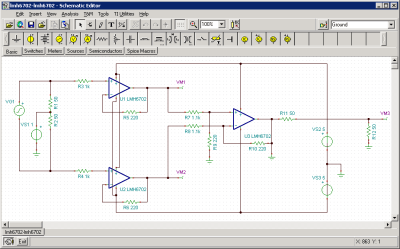

This probe design is little more than a 3D printed case, an old power supply toroid, and a conventional alligator clamp to make the business end. The sensor uses a ferrite core and a hall effect sensor. The ferrite toroid is split in half, one half in each side of the clamp. An opamp circuit provides a gain of 100 to boost the hall effect sensor’s output.

In addition to building a homebrew probe, the video also shows a teardown of a Hantek current probe and explains the theory behind the different kinds of current probes, including some tricks like using a compensation winding to prevent core magnetization.

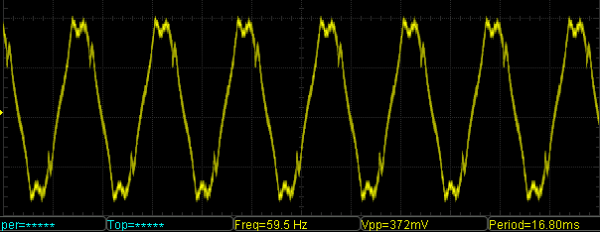

Does it work? You bet. After calibration, it did just fine. It’s not as pretty as a $100 unit, but beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and we are suckers for homebrew gear so we will say it is certainly more interesting. If you have a fair junk box (and a 3D printer), this probe could be made very inexpensively. The hall effect and a BNC connector are likely to be the most expensive parts. Even if you bought everything and used a non-printed case, we would be hard-pressed to think you’d spend more than $25.

If you want to see how the big boys do it, Keysight had a good break down last year. We’ve seen other homebrew builds for current probes and some of them are very accurate.

Continue reading “Make Your Own Current Clamp Probe” →

![A selection of probes, from [Jim Williams'] Linear Technology app note 72.](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/lt-probe-configurations.jpg?w=400)