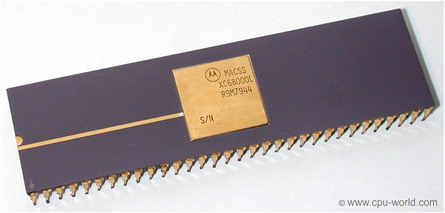

Introduced in 1979, the Motorola 68000 CPU was first used in very expensive and very high-end workstations from the likes of Sun and SGI. As the processor matured it became well-known for its use in the original Macintosh, early Amigas, and even the TI-89 graphing calculator and a few video game consoles such as the Sega Genesis and Atari Jaguar.

A few days ago when I posted a homebrew computer build based on the 65816 CPU, I lamented the lack of builds using the venerable Motorola 68k. Hackaday readers were quick to point out the many homebrew computers making use of this classic CPU, and I’m glad to post them here.

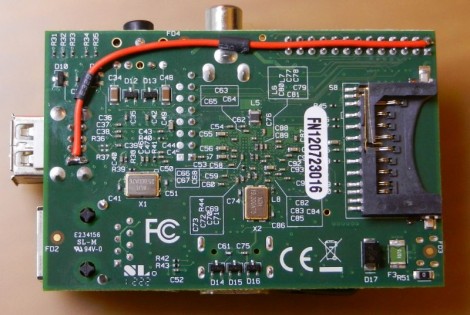

First up is an amazing 68008 build featuring an IDE disk interface, a floppy disk interface, 10base-T Ethernet connectivity, a real-time clock, and two SID synthesizer chips. As far as features go, this build takes the cake. Pity I can’t find a writeup.

Here’s a 68000-based computer built around the S-100 bus. Like the first computer to use the S-100 bus, the Altair 8800, this computer is plugged into a backplane that breaks out the data, address, and interrupt lines to every device on the bus.

Of course, no mention of backplane computers would be complete without a Eurocard version. [N8VEM] built a 68000 computer able to be plugged in to a backplane along with an IDE controller card and a display controller.

Finally, in true ‘giant mess of wires’ spirit, [Dajgoro] sent in his 68k single board computer featuring 512 kB of RAM and a 16k ROM. [Dajgoro] also took the time to wire in a PIC microcontroller, allowing him to expand his computer far beyond what vintage components would allow.

The 68k was – and still is – a very powerful CPU that far surpasses the capabilities of the 6502 and Z80 homebrew computers we see from time to time. Short of building a 486 or Pentium-based computer from scratch, building a 68k machine is one of the crowning achievements of hardware hackery, and something we hope to see more of in the future.