When a Lexmark inkjet printer stopped working, [Mojobobo] was able to claim it as his own. He quickly realized that the machine was flooded with ink and not worth repairing, but that didn’t mean he couldn’t still find a use for it. When he learned that the printer’s firmware was not only upgradable but also unprotected, he knew he should be able to get the printer to do his own bidding.

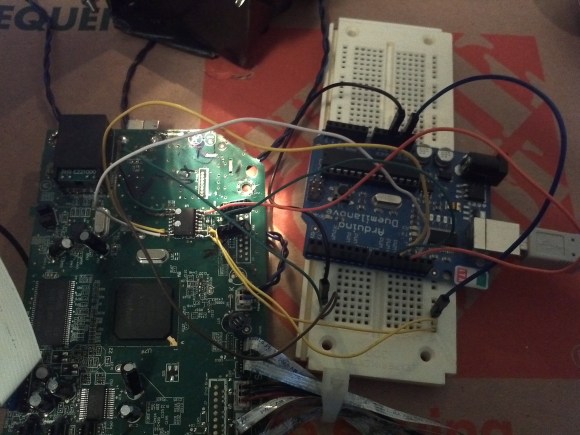

[Mojobobo] started his journey with the motherboard. The unit still powered up, but it was asking to insert a “duplex module” before it would boot any further. [Mojobobo] first tried to find a way to trick the duplex module sensor, but was unsuccessful. His next step was to search for some kind of serial communications port. He didn’t have an oscilloscope, so instead he used a speaker with a wire probe. In theory, if the wire was pressed against an active serial port, he would be able to hear varying tones through the speaker. Sure enough, he found some interesting tones after probing around some ports next to a “JTAG” label. He looked up some information about the nearby chip and found that it included an SPI bus.

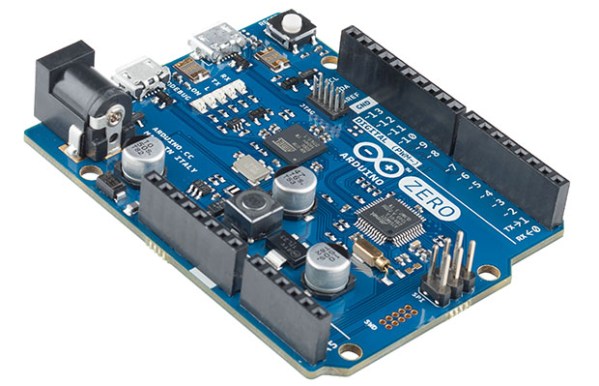

After some internet research, [Mojobobo] learned enough about SPI to have a rough idea of how to use it. Having limited tools available to him, he decided to use his Arduino to try to communicate with the motherboard. After wiring up a simple circuit, (and then re-wiring it) he was able to dump the first 4096 bytes of the motherboard’s boot loader to the Arduino via the SPI interface.

[Mojobobo’s] next steps will be to find a faster way to dump the boot loader. At 9600 baud, he grew tired of waiting after three hours. Once he has the full boot loader he intends to search for a way to bypass the duplex sensor and get the board to finish booting. Then he may just use the printer for its scanning functions, or he might find other interesting uses for it.

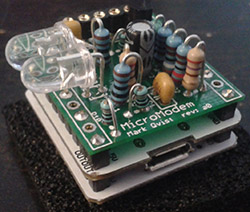

Them kids with those Arduinos don’t know what they’re missing. A serial connection is just too easy, and there’s so much fun to be had with low bandwidth modems. [Mark]

Them kids with those Arduinos don’t know what they’re missing. A serial connection is just too easy, and there’s so much fun to be had with low bandwidth modems. [Mark]