The image of the crackpot inventor, disheveled, disorganized, and surrounded by the remains of his failures, is an enduring Hollywood trope. While a simple look around one’s shop will probably reveal how such stereotypes get started, the image is largely not a fair characterization of the creative mind and how it works, and does not properly respect those who struggle daily to push the state of the art into uncharted territory.

That said, there are plenty of wacky ideas that have come down the pike, most of which mercifully fade away before attracting undue attention. In times of war, though, the need for new and better ways to blow each other up tends to bring out the really nutty ideas and lower the barrier to revealing them publically, or at least to military officials.

Of all the zany plans that came from the fertile minds on each side of World War II, few seem as out there as a plan to use birds to pilot bombs to their targets. And yet such a plan was not only actively developed, it came from the fertile mind of one of the 20th century’s most brilliant psychologists, and very nearly resulted in a fieldable weapon that would let fly the birds of war.

Feedback Control

After graduating from college in 1926, Burrhus Frederic Skinner was a bit of a lost soul. He had had every intention of being a writer, but nothing seemed to be coming from his efforts. Living in his parents’ Pennsylvania home, he decided to scrap his plan of writing the Great American Novel and return to school.

Inspired by the works of Pavlov and Watson, which he browsed while working at a bookstore to make ends meet, B.F. Skinner applied to the Psychology Department of Harvard University in 1926. Skinner was interested in making psychology an experimental science, and rather than concentrating on exploring the mind, he was determined to only study what could be quantified. Instead of trying to delve into the subjective world of thoughts and emotions, he decided to study behaviors.

Anyone who has taken an introductory psychology course will be familiar with “operant conditioning,” the term Skinner came up with to describe one way that animals learn. The idea with operant conditioning is that behaviors are either reinforced or discouraged by what happens as a result of the behavior. The classic case occurs in the Skinner Box, an invention of his. In the simplest case, a rat placed in the box can be trained to press a lever by the release of a food pellet, or can be discouraged from pressing the lever by getting an electric shock through the cage floor. Operant conditioning differs from classical conditioning, such as in the case of Pavlov’s famously drooling dogs, in that the latter makes an association between stimulus and an involuntary response, like salivating at the sound of a bell, while the former deals with voluntary behaviors, like pressing a lever.

By the 1940s, B.F. Skinner had spent years studying operant conditioning on a variety of model organisms, using dozens of instruments of his own devising to quantify behavior. With war raging around the globe, Skinner pondered the devastation caused by bombing campaigns, which relied on massive quantities of bombs to make up for the lack of precision in the aiming. He wondered if there would be any way to guide a bomb or missile to its target, and hit upon the idea of using one of the stars of his operant conditioning boxes — pigeons. Easily trained and with excellent eyesight, pigeons might make a workable guidance system for ordnance.

Project Pigeon

Skinner set to work in his lab with a few pigeons he bought from a poultry store. He first pictured a restrained bird controlling guidance fins on the bomb using head movements. Stuffed into a harness made from a sock with a hole cut in the toe, the bird would watch the approaching target and effect control while moving its head to keep the target centered in a window in the projectile’s nose. He tested his idea with a complicated gantry system whose motors were controlled by the bird’s movements and found that a properly conditioned pigeon could control its position well enough to arrive on target — a food bowl with some seeds — as the gantry was pushed across the room. The idea had promise.

Skinner began to sell his idea around, but not surprisingly, he was rebuffed. Even the National Research Defense Committee (NRDC), a clearinghouse for all manner of crackpot ideas to aid the war effort, turned him down. Skinner pressed on, though, improving his system and meticulously recording his results. Eventually, he got the attention of the right people and was awarded a contract to develop the idea further. In a sign of just how little esteem the War Department held Skinner’s idea, the effort was dubbed “Project Pigeon,” with no effort to conceal its nature.

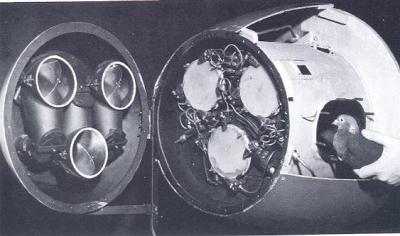

Project Pigeon centered around 64 birds trained using the same techniques as his first cohort. Rather than use head movements directly, though, Skinner switched to training the birds to peck at the target to keep it centered in their field of view. The conditioned birds would peck wildly at the screen, with the idea that the pecking would be translated into electrical control signals. Sadly, though, before the control system was developed, the military cut funding to the program to direct funds to projects that were more likely to deliver. Project Pigeon was no more.

The Return of the Pigeons

Skinner was disappointed by what he thought was the shortsightedness of the War Department brass. But Project Pigeon still had some surprises to deliver. Skinner kept the 64 pigeons and some of his test apparatus, which he used to test the birds over the next few years. Without any further training, the birds were all able to perform to the level they attained during the program, as many as six years later. Skinner felt that this proved his methods, and gave him valuable insights into operant conditioning, which he applied to his research.

After the war, the project was resurrected as a Cold War effort by the Navy to target Soviet ships at sea. Skinner’s principles were put to the test under Project Orcon, for “organic control,” with trios of pigeons stuffed into the nosecones of missiles. Technology had advanced a bit in the intervening years, such that the birds could peck directly at a conductive glass window with a beak-mounted metal tab; the three birds were to work together to guide the missile onto the target.

Project Orcon had some successful tests under ideal conditions, but the lack of real-world usability and developments in electronic guidance resulted in the project being killed in 1953. But the legacy of Skinner’s pigeons lived on, with the principle used to rescue lost fisherman with pigeons trained for aerial search missions. This along with the practical test of Skinner’s operant conditioning theories was the real benefit of Project Pigeon, and is perhaps a better ending than anyone imagined for such a crazy idea.

Thanks to [Gervais] for the idea for this article.

Why didn’t they try lawyers instead?

People hate them even more than pigeons, and animal rights activists wouldn’t get mad.

+1

Dropping lawyers on the enemy could be considered a War Crime.

1++

Considered a form of salting the earth.

Lawyers will bring the greatest president ever, down.

President Dwayne Elizondo Mountain Dew Herbert Camacho ?

Vote for Pedro.

Do you know what Lawyers charge per hour!?

Three lawyers guiding a missile? It wont even exit he silo

And now I’m hungry for some chicken.

Not Squab?

Well, in WWII in the Japan theater they did actually deploy incendiary bats. Yes, these were real bats armed with an incendiary device that would go off once the bat roosted up in the eaves of a house or building made of highly flammable paper. These were one-way missions and I don’t think any of the bats ever returned from one. I always found this interesting that first, someone had to think of this idea in the first place, and then, they had to convince many others in the chain of command to actually do it. Evidently, they worked pretty well.

Human arsonists would have been better.

The bat bomb was never deployed.

Yes it was, I spoke to an old vet who was involved with that program and it was very successful…according to him. Of course, he passed away some time ago now.

Well, according to Google you are right. It says the atomic bomb made this project obsolete and it was cancelled. Oh well…I suppose the old fellow had not remembered exactly right but, at least they really did work on this as a real project for a while.

IIRC, a full scale replica Japanese village was built and the bat bomb was tested there to devastatingly effective results.

‘The Bomb’ put an end to development or deployment though.

According to what I’ve read, the 1st test burnt down the military base of the guys testing it… unintended consequences and all that.

Can’t remember if it got used in anger but think the comment about being made obsolete by the atomic bomb is pretty accurate.

Yes, it appears you are correct.

That explains a good deal…

https://cdn.theatlantic.com/assets/media/img/mt/2014/10/batboy1_1/lead_large.jpg?1522685246

I thought the Bat bomb was the one that starred George Clooney.

Nice.

Maybe future autonomous vehicles will be pigeon powered?

I can just see a flock of autonomous vehicles following pedestrians around Lord Nelson’s column.

B^)

ObMontyPythonskit link:

https://youtu.be/GsVamVhGwsU?t=76

Perhaps I’m exposing my ignorance, but don’t pigeons return home? Or is that a special species called homing pigeons? I wasn’t aware that they just fly where they are instructed to fly. In this case, the bombs they would guide would quite possibly accomplish nothing short of blowing their commanders, at home base, into the Hall of Darwin Awards Fame.

Yes, Homing Pigeons are a different kind of pigeon.

You missed my sarcasm. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_pigeon War pigeons, carrier pigeons whatever you want to call them, were homing pigeons.

Pigeons are pigeons. Any pigeon want to get home if it has squabs or even a high status female mate. Breeding have increased their stamina and navigation skills, but all of them want to return home. I once had my loft invaded by hobos and I had to drive 40 miles and release them before they didn’t come back.

Okay, I admit my ignorance on that!

These pigeons weren’t actually flying, in the classical sense. They were locked in a little compartment at the front of a missile, trying to line up a transparency of the target with the actual target behind it by pressing little up, down, left and right buttons. And succeed or fail, their reward was to be in the next world. Oddly enough there was a shortage of human volunteers to take their place.

I belive they where trainee to peck in the boat in a display with resistance touch. In the lab they got food when they pecked on the target boat.

All they wanted was a pigeon guided missile, got this instead:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KJJW7EF5aVk

:o)

The Coyote was one of our great unsung hackers.

Good at “taking one for the team”.

I met one of his students a number of years ago [mid-70’s]. The student, then teacher also worked in the physiology field,

and ran into an interesting problem: When you describe an experiment [for example: after the rat presses the lever, a light goes on, a bell rings and a food pellet is dropped into the bowl], what is the sequence of actions, do they happen one after the other, how long a delay between, etc. He developed a state machine language [called ‘sked’ if I remember correctly], that was used to define experiments like this so that the experiment could be documented and repeated. He even wrote a compiler for the language,,

This would be a good meme for a sci fi movie. Maybe “Avengers 8, the Return of the Pigeons” :)

Olga, a regent of Ancient Rus, supposedly burned the capital of a hostile tribe using sparrows and pigeons she had received from that city as a tribute. She had pieces of burning sulfur tied to the birds, and when they were released, they flew to their nests, setting them (and nearby houses) on fire. So that’s one design of a pigeon-controlled incendiary bomb.

I heard that the Russians tried this with dogs during WW2, except in battle they’d get scared and run under the Russian tanks instead of the enemy ones.

The dogs were trained on Russian Tanks so when released in battle they naturally ran for the target they were trained for, Russian Tanks!

Maybe those dogs were German shepherd.

:o)

Given the advent of IOT, and the fact that it’s giving rise something genuinely akin to “ubiquitous computing”, we could be looking at a golden age for the creation of workable cyborgs. There are already projects where MCUs steer giant cockroaches, no reason the relationship could not be reversed and/or made bidirectional (e.g. computer controls “strategic” goal, organism handles “tactical” elements at the local level).

Devices are small, connected, wireless, cheap and packed everyday with more and more instrumentation .. and networks are literally everywhere .. so integrating “devices” with “organic agents” is low hanging fruit. In fact, most wearable tech could probably be considered part of this space. Even mobile computing could be considered part of this space .. we already have a bit of a “cyber-allelomimetic” relationship with our phones.

Let the Tin Foil Hat replies begin! This article has gotten me in touch with my inner crack-pot .. hopefully, this particular crack opens into a pot full of interesting ideas.

It wouldn’t be that hard to fashion a vest for a rat or something with wireless communication, a camera and a couple vibration motors – with enough training you have a remote controlled fpv rat

What you have to remember is that bomb targetting was rough and ready to say the least during WW2. I can’t remember the figure off the top of my head but I think I saw that only 20% of bombs actually “hit” the target they were aimed at. And they only got to that 20% figure by having a pretty generous definition of the word “hit” as meaning landed no more than 5 miles away. Better navigation only gets you so far, they needed something to improve the accuracy on that last little bit of the journey, and pigeons was as good as anything else they had at the time.

Feedback Control

Project Pigeon

The Return of the Pigeons

I demand this be made into a Film Trilogy

With pre-quels and spin-offs!

I thought once if a guided-rat with no invasive electrodes could be developed using Skinner’s conditioning technics.

I attended Navy guided missile school in Dam Neck, VA and Pomona, CA in 1959 – 60. We were shown a film of the pigeon directed missile test. It wasn’t claimed to be a real thing, something to chuckle at as one of the more “creative” control systems.

News: litter bugs being bombed all over the world

Exploding Mad Cows.

“While much of the world shuns British cows, a Cambodian newspaper suggested today that the animals be shipped to Cambodia and allowed to roam free to detonate the millions of land mines littering the country.

“The English have 11 million mad cows and Cambodia has roughly the same number of equally mad land mines,” The Cambodia Daily said. “Surely the solution to Cambodia’s mine problem is here before our very eyes in black and white.”

https://www.nytimes.com/1996/03/30/world/cannon-fodder.html