Merry Christmas and happy New Year! After a week off, we have quite a few stories to cover, starting with an unexpected Christmas gift from Apple. Apple has run an invitation-only bug bounty program for years, but it only covered iOS, and the maximum payout topped out at $200K. The new program is open to the public, covers the entire Apple product lineup, and has a maximum payout of $1.5 million. Go forth and find vulnerabilities, and make sure to let us know what you find.

ToTok

The United Arab Emirates had an odd policy regarding VoIP communications. At least on mobile networks, it seems that all VoIP calls are blocked — unless you’re using a particular app: ToTok. Does that sound odd? Is your “Security Spider Sense” tingling? It probably should. The New York Times covered ToTok, claiming it was actually a tool for spying on citizens.

While that coverage is interesting, more meat can be found in [Patrick Wardle]’s research on the app. What’s most notable, however, is the distinct lack of evidence found in the app itself. Sure, ToTok can read your files, uploads your contact book to a centralized server, and tries to send the device’s GPS coordinates. This really isn’t too far removed from what other apps already do, all in the name of convenience.

It seems that ToTok lacks end-to-end encryption, which means that calls could be easily decrypted by whoever is behind the app. The lack of malicious code in the app itself makes it difficult to emphatically call it a spy tool, but it’s hard to imagine a better way to capture VoIP calls. Since those articles ran, ToTok has been removed from both the Apple and Google’s app stores.

SMS Keys to the Kingdom

Have you noticed how many services treat your mobile number as a positive form of authentication? Need a password reset? Just type in the six-digit code sent in a text. Prove it’s you? We sent you a text. [Joakim Bech] discovered a weakness that takes this a step further: all he needs is access to a single SMS message, and he can control your burglar alarm from anywhere. Well, at least if you have a security system from Alert Alarm in Sweden.

The control messages are sent over SMS, making them fairly accessible to an attacker. AES encryption is used for encryption, but a series of errors seriously reduces the effectiveness of that encryption. The first being the key. To build the 128-bit encryption key, the app takes the user’s four-digit PIN, and pads it with zeros, so it’s essentially a 13 bit encryption key. Even worse, there is no message authentication built in to the system at all. An attacker with a single captured SMS message can brute force the user’s PIN, modify the message, and easily send spoofed commands that are treated as valid.

Microsoft Chrome

You may have seen the news, Microsoft is giving up on their Edge browser code, and will soon begin shipping a Chromium based Edge. While that has been a source of entertainment all on its own, some have already begun taking advantage of the new bug bounty program for Chromium Edge (Edgium?). It’s an odd bounty program, in that Microsoft has no interest in paying for bugs found in Google’s code. As a result, only bugs in the Edge-exclusive features qualify for payout from Microsoft.

As [Abdulrahman Al-Qabandi] puts it, that’s a very small attack surface. Even so, he managed to find a vulnerability that qualified, and it’s unique. One of the additions Microsoft has made to Edgium is a custom new tab page. Similar to other browsers, that new tab page shows the user their most visited websites. The problem is that the site’s title is shown on that page, but without any sanity checking. If your site’s title field happens to include Javascript, that too is injected into the new tab page.

The full exploit has a few extra steps, but the essence is that once a website makes it to the new tab page, it can take over that page, and maybe even escape the browser sandbox.

Chrome Password Checkup

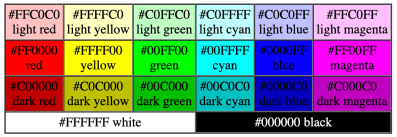

This story is a bit older, but really grabbed my attention. Google has rolled a feature out in Chrome that automatically compares your saved passwords to past data breaches. How does that work without being a security nightmare? It’s clever. A three-byte hash of each username is sent to Google, and compared to the hashes of the compromised accounts. A encrypted database of potential matches is sent to your machine. Your saved passwords, already encrypted with your key, is encrypted a second time with a Google key, and sent back along with the database of possible matches, also encrypted with the same Google key. The clever bit is that once your machine decrypts your database, it now has two sets of credentials, both encrypted with the same Google key. Since this encryption is deterministic, the encrypted data can be compared without decryption. In the end, your passwords aren’t exposed to Google, and Google hasn’t given away their data set either.

The Password Queue

Password changes are a pain, but not usually this much of a pain. A university in Germany suffered a severe malware infection, and took the precaution of resetting the passwords for every student’s account. Their solution for bootstrapping those password changes? The students had to come to the office in person with a valid ID to receive their new passwords. The school cited German legal requirements as a primary cause of the odd solution. Still, you can’t beat that for a secure delivery method.