Sometimes in fantasy fiction, you don’t want to explain something that seems inexplicable, so you throw your hands up and say, “A wizard did it.” Sometimes in astronomy, instead of a wizard, the answer is dark matter (DM). If you are interested in astronomy, you’ve probably heard that dark matter solves the problem of the “missing mass” to explain galactic light curves, and the motion of galaxies in clusters.

Now [Pedro De la Torre Luque] and others are proposing that DM can solve another pair of long-standing galactic mysteries: ionization of the central molecular zone (CMZ) in our galaxy, and mysterious 511 keV gamma-rays.

The Central Molecular Zone is a region near the heart of the Milky Way that has a very high density of interstellar gases– around sixty million times the mass of our sun, in a volume 1600 to 1900 light years across. It happens to be more ionized than it ought to be, and ionized in a very even manner across its volume. As astronomers cannot identify (or at least agree on) the mechanism to explain this ionization, the CMZ ionization is mystery number one.

Mystery number two is a diffuse glow of gamma rays seen in the same part of the sky as the CMZ, which we know as the constellation Sagittarius. The emissions correspond to an energy of 515 keV, which is a very interesting number– it’s what you get when an electron annihilates with the antimatter version of itself. Again, there’s no universally accepted explanation for these emissions.

So [Pedro De la Torre Luque] and team asked themselves: “What if a wizard did it?” And set about trying to solve the mystery using dark matter. As it turns out, computer models including a form of light dark matter (called sub-GeV DM in the paper, for the particle’s rest masses) can explain both phenomena within the bounds of error.

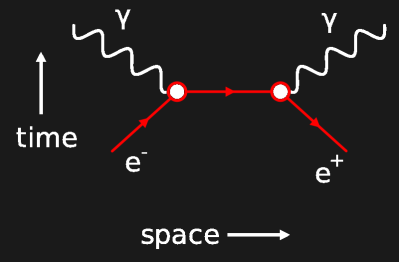

In the model, the DM particles annihilate to form electron-positron pairs. In the dense interstellar gas of the CMZ, those positrons quickly form electrons to produce the 511 keV gamma rays observed. The energy released from this annihilation results in enough energy to produce the observed ionization, and even replicate the very flat ionization profile seen across the CMZ. (Any other proposed ionization source tends to radiate out from its source, producing an uneven profile.) Even better, this sort of light dark matter is consistent with cosmological observations and has not been ruled out by Earth-side dark matter detectors, unlike some heavier particles.

Further observations will help confirm or deny these findings, but it seems dark matter is truly the gift that keeps on giving for astrophysicists. We eagerly await what other unsolved questions in astronomy can be answered by it next, but it leaves us wondering how lazy the universe’s game master is if the answer to all our questions is: “A wizard did it.”

We can’t talk about dark matter without remembering [Vera Rubin].