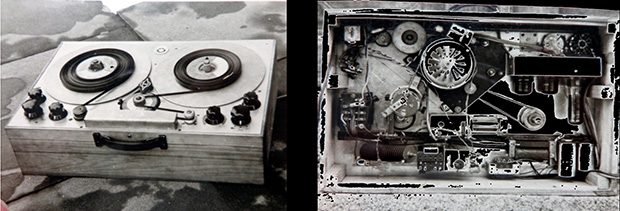

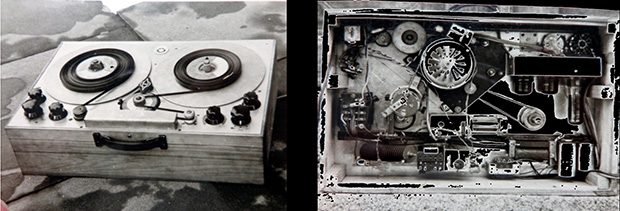

After telling a few stories about how he built a tape recorder as a 16-year-old boy in post-war Germany, [Hans] was finally cajoled into retelling this story in a proper form, giving the Internet one more example of how clever old-school tinkerers could be.

In 1949, [Hans] was but a wee lad of 16 and having built a crystal and tube radio set at 13 and 14 respectively desperately wanted a tour of the local radio station in Hamburg. A kind engineer responded to a letter and a month after requesting a tour [Hans] and his friend found themselves being guided around a proper radio station. One of the most impressive pieces of technology at the time was a tape recorder, which the engineer demonstrated by recording and playing back the voices of [Hans] and his friend. This was the first time [Hans] had ever heard his voice played back and instantly knew he needed to build one of these for himself.

Technical details on the theory and operation of a tape recorder were sparse, but [Hans] managed to come up with an amplifier, tape transport mechanism, a recording and playback head, and homemade magnetic tape made from a reel of iron filings glued to a reel of 8mm film stock.

Testing the equipment, [Hans] and his friend found the device simply wouldn’t work; the homemade magnetic tape was simply too thick, and you couldn’t just go out and buy a reel of magnetic tape. Undeterred, they mailed BASF, the only manufacturer of magnetic tape, and after a month received a 1000m reel of tape.

With tape that worked, [Hans] set about improving his recorder with a tape transport mechanism built from a turntable and a new recording head. This time, his tape recorder worked. When word got around of this amazing machine that could record music, [Hans] was invited to record the local symphony and the speeches for a senior group.

The first commercial reel to reel recorders were released in Germany a little more than a year after [Hans] completed his project, making this one of the more impressive DIY projects we’ve seen.