First, it was the WiFi router: my ancient WRT54G that had given me nearly two decades service. Something finally gave out in the 2.4 GHz circuitry, and it would WiFi no more. Before my tears could dry, our thermometer went on the fritz. It’s one of those outdoor jobbies that transmits the temperature to an indoor receiver. After that, the remote for our office lights stopped working, but it was long overdue for a battery change.

Meanwhile, my wife had ordered a new outdoor thermometer, and it too was having trouble keeping a link. Quality control these days! Then, my DIY coffee roaster fired up once without any provocation. This thing has worked quasi-reliably for ten years, and I know the hardware and firmware as if I had built them myself – there was no way one of my own tremendously sophisticated creations would be faulty. (That’s a joke, folks.) And then the last straw: the batteries in the office light remote tested good.

We definitely had a poltergeist, a radio poltergeist. And the root cause would turn out to be one of those old chestnuts from the early days of CMOS ICs – never leave an input floating that should have a defined logic level. Let me explain.

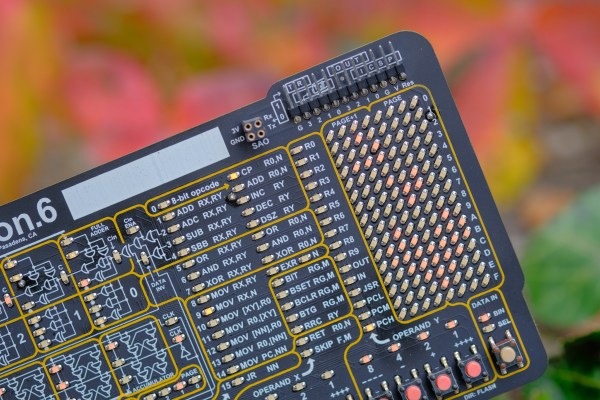

The WRT54G was the hub of my own home automation system, an accretion of ESP8266 and other devices that all happily speak MQTT to each other. When it went down, none of the little WiFi nodes could boot up right. One of them, described by yours truly in this video, is an ESP8266 connected to a 433 MHz radio transmitter. Now it gets interesting – the thermometers and the coffee roaster and the office lights all run on 433 MHz.

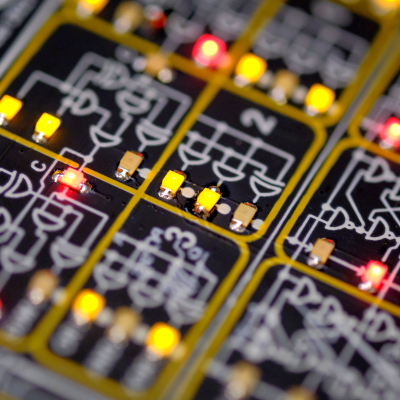

Here’s how it went down. The WiFi-to-433 bridge failed to connect to the WiFi and errored out before the part of the code where it initialized GPIO pins. The 433 MHz transmitter was powered, but its digital input was left flopping in the breeze, causing it to spit out random data all the time, with a pretty decent antenna. This jammed everything in the house, and apparently even once came up with the command to turn on the coffee roaster, entirely by chance. Anyway, unplugging the bridge fixed everything.

This was a fun one to troubleshoot, if only because it crossed so many different devices at different times, some homebrew and some commercial, and all on different control systems. Until I put it together that everything on 433 MHz was failing, I hadn’t even thought of it as one event. And then it turns out to be a digital electronics classic – the dangling input!

Anyway, hope you enjoyed the ride. And spill some copper for the humble pull-down resistor.