We’re back in Europe for this week’s Hackaday podcast, as Elliot Williams is joined by Jenny List. In the news this week is the passing of Ed Smylie, the engineer who devised the famous improvised carbon dioxide filter that saved the Apollo 13 astronauts with duct tape.

Closer to home is the announcement of the call for participation for this year’s Hackaday Supercon; we know you will have some ideas and projects you’d like to share.

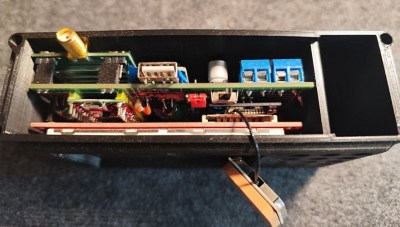

Interesting hacks this week include a new Mac Plus motherboard and Doom (just) running on an Atari ST, while a LoRa secure messenger and an astounding open-source Ethernet switch captivated us on the hardware front. We also take a dive into the Mouse programming language, a minimalist stack-based environment from the 1970s. Among the quick hacks are a semiconductor dopant you can safely make at home, and a beautiful Mac Mini based cyberdeck.

Finally, we wrap up with our colleague [Maya Posch] making the case for a graceful degradation of web standards, something which is now sadly missing from so much of the online world, and then with the discovery that ChatGPT can make a passable show of emulating a Hackaday scribe. Don’t worry folks, we’re still reassuringly meat-based.

As you’ll no doubt be aware, these large language models work by gathering a vast corpus of text, and doing their computational tricks to generate their output by inferring from that data. They can thus create an artwork in the style of a painter who receives no reward for the image, or a book in the voice of an author who may be struggling to make ends meet. From the viewpoint of content creators and intellectual property owners, it’s theft on a grand scale, and you’ll find plenty of legal battles seeking to establish the boundaries of the field.

As you’ll no doubt be aware, these large language models work by gathering a vast corpus of text, and doing their computational tricks to generate their output by inferring from that data. They can thus create an artwork in the style of a painter who receives no reward for the image, or a book in the voice of an author who may be struggling to make ends meet. From the viewpoint of content creators and intellectual property owners, it’s theft on a grand scale, and you’ll find plenty of legal battles seeking to establish the boundaries of the field.