[MSylvain59] likes to tear down old surplus, and in the video below, he takes apart a German transceiver known as a U-600M. From the outside, it looks like an unremarkable gray box, especially since it is supposed to work with a remote unit, so there’s very little on the outside other than connectors. Inside, though, there’s plenty to see and even a few surprises.

Inside is a neatly built RF circuit with obviously shielded compartments. In addition to a configurable power supply, the radio has modules that allow configuration to different frequencies. One of the odder components is a large metal cylinder marked MF450-1900. This appears to be a mechanical filter. There are also a number of unusual parts like dogbone capacitors and tons of trimmer capacitors.

The plug-in modules are especially dense and interesting. In particular, some of the boards are different from some of the others. It is an interesting design from a time predating broadband digital synthesis techniques.

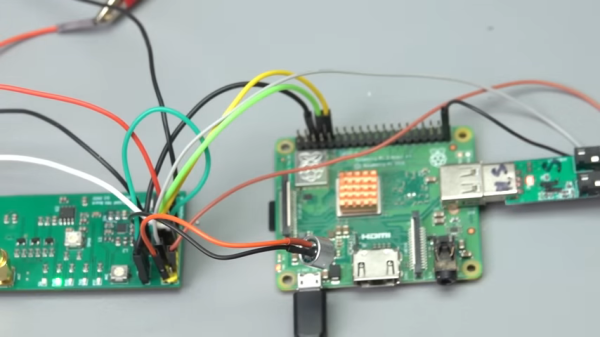

While this transceiver is stuffed with parts, it probably performs quite well. However, transceivers can be simple. Even more so if you throw in an SDR chip.