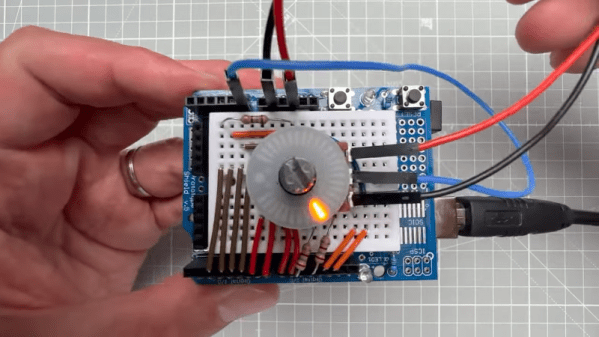

Sometimes, a hack isn’t really about the technology but about the logistics. If we asked you to light up an LED using an Arduino, there’s a good chance you’d know exactly how to do that. How about a bunch of LEDs? Simple. Now turn on LEDs proportional to an input voltage. A little harder, but nothing that you probably haven’t done a million times. Finally, arrange the LEDs in an attractive circle around a potentiometer. Wait, how are you going to do that? [Upir] shows us a ready-made ring light for just this purpose and you can see the beautiful thing in the video below.

We made the LED things sound slightly easier than it is. The ring light has 31 LEDs but only 12 pins, so there is some multiplexing going on. The modules come in pairs for about $20, so not a throwaway part, but they will really dress up anything that needs a knob of any kind.

Naturally, it doesn’t matter what you use to drive the LEDs. You could track a pot or a rotary encoder. Or you could show microphone levels or something else. After all, it is just a bunch of LEDs. For that matter, they’d probably make a good pair of robot eyes. Let us know what you want to use them for in the comments.

If your significant other is a little geeky, you might want a different kind of ring light. We couldn’t help but wish the LEDs on the ring were addressable. That would open up a world of interesting possibilities while reducing the pin count, too.