The history of Commodore 8-bit computers ends with a fantastically powerful, revolutionary, and extraordinarily collectible device. The Commodore 65 was the chicken lip’ last-ditch effort to squeeze every last bit out of the legacy of the Commodore 64. Basically, it was a rework of a 10-year-old design, adding advanced features from the Amiga, but still retaining backwards compatibility. Only 200 prototypes were produced, and when these things hit the auction block, they can fetch as much as an original Apple I.

For their Hackaday Prize entry, resident hackaday.io FPGA wizard [Antti Lukats] and a team of retrocomputing enthusiasts are remaking the Commodore 65. Finally, the ultimate Commodore 8-bit will be available to all. Not only is this going to be a perfect replica of what is arguably the most desirable 8-bit computer of all time, it’s going to have new features like HDMI, Ethernet, and connections for a lot of FPGA I/O pins.

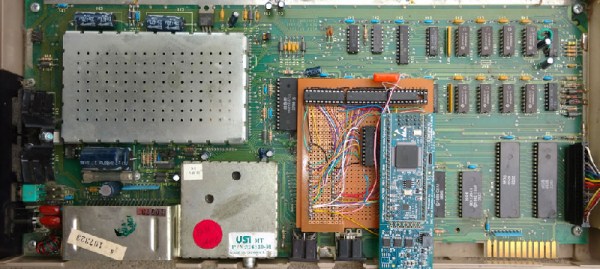

The PCB for this project is designed to fit inside the original case and includes an Artix A200T FPGA right in the middle of the board. HDMI and VGA connectors fill the edges of the board, there’s a connector for a floppy disk, and the serial port, cartridge slot, and DE9 joystick connectors are still present.

You can check out an interview from the Mega65 team below. It’s in German, but Google auto-generated and auto-translated captions actually work really, really well.

Here at the Vintage Computer Festival, we’ve found oodles of odds and ends from the past. Some, however, have gotten a modern twist like [bitfixer’s] recent Commodore PET project upgrades.

Here at the Vintage Computer Festival, we’ve found oodles of odds and ends from the past. Some, however, have gotten a modern twist like [bitfixer’s] recent Commodore PET project upgrades.