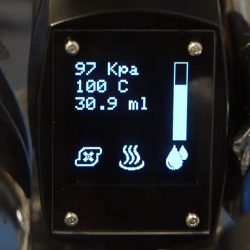

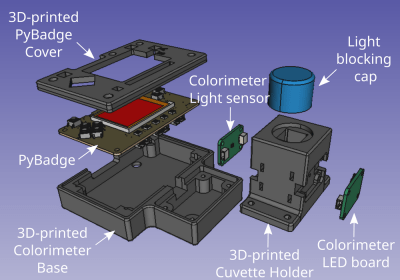

The 10BASE-T1 Ethernet standard is also known as ‘single pair Ethernet’ (SPE), as it’s most defining feature is the ability to work over a single pair of conductors. Being fairly new, it offers a lot of advantages where replacing existing wiring is difficult, or where the weight of the additional conductors is a concern, such as with the underwater sensor node project that [Michael Orenstein] and [Scott] dreamed up and implemented as part of a design challenge. With just a single twisted pair, this sensor node got access to a full-duplex 10 Mbit connection as well as up to 50 watts of power.

The SPE standards (100BASE-T1, 1000BASE-T1 and NGBASE-T1) 10BASE-T1 can do at least 15 meters (10BASE-T1S), but the 10BASE-T1L variant is rated for at least 1 kilometer. This makes it ideal for a sensor that’s placed well below the water’s surface, while requiring just the single twisted pair cable when adding Power over Data Lines (PoDL). Whereas Power-over-Ethernet (PoE) uses its own dedicated pairs, PoDL piggybacks on the same wires as the data, requiring it to be coupled and decoupled at each end.

Continue reading “Underwater Sensor Takes Single Pair Ethernet For A Dip”