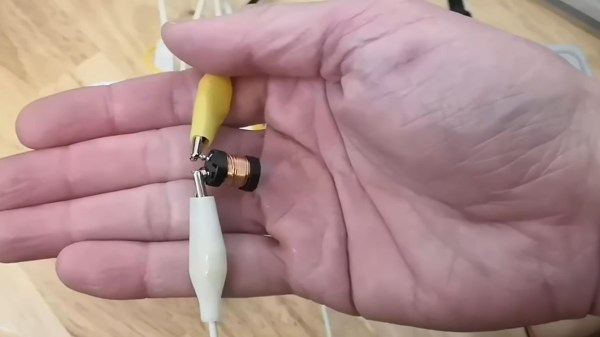

If you’re familiar with electrical slip rings as found in motors and the like you’ll know them as robust assemblies using carefully chosen alloys and sintered brushes, able to take the load at high RPM for a long time. But not all slip ring applications need this performance. For something requiring a lot less rotational ability, [Luke J. Barker] has something from his parts bin, and probably yours too. It’s an audio jack.

On the face of it, a 1/4″ jack might seem unsuitable for this task, being largely a small-signal audio connector. But when you consider its origins in the world of telephones it becomes apparent that perhaps it could do so much more. It works for him, but we’d suggest if you’d like to follow his example, to use decent quality plugs and sockets.

This is an entry in our 2025 Component Abuse Challenge, and we like it for thinking in terms of the physical rather than the electrical. The entry period for this contest will have just closed by the time you read this, so keep an eye out for the official results soon.