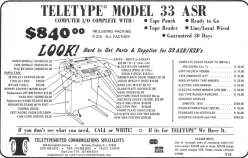

The Apple II was at the forefront of the home computer revolution when it came out in 1977. In its era, nobody really cared about hooking up the Apple II to a VGA monitor, but these days, it’s far easier than sourcing an original monitor. The V2 Analog is a useful tool that will let you do just that, plus some other neat tricks, besides.

As demonstrated on Youtube by [Adrian’s Digital Basement], The V2 Analog is basically a slot-in video card for the Apple II, II+, and IIe. It’s based upon the AppleII-VGA, which uses a Raspberry Pi Pico to snoop the 6502 CPU bus and copy the video memory. It then outputs a high-quality VGA signal that is far nicer than the usual composite output options.

As a bonus, the V2 Analog can be reconfigured to run as an emulated AppliCard Z80 expansion card instead. This card was originally intended to allow Apple II users to run CP/M applications. The V2 Analog does a great job in this role, though it bears noting it can’t handle VGA output and Z80 emulation at the same time.

Project files are available on Github for the curious. The Apple II may be long out of production, but it’s certainly not forgotten. Video after the break.

Continue reading “An Easy Z80 And VGA Upgrade For The Apple II”

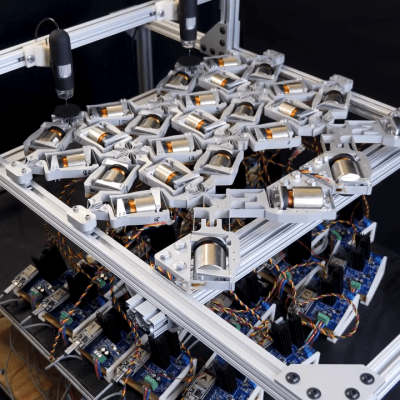

The printer is a gargantuan thing, using an aluminium frame and a familiar Cartesian layout. It boasts a build volume of 1110 mm x 1110 mm x 2005 mm, making it more than big enough to print human-sized statues. Dogs, cats, and some great apes may be possible, too.

The printer is a gargantuan thing, using an aluminium frame and a familiar Cartesian layout. It boasts a build volume of 1110 mm x 1110 mm x 2005 mm, making it more than big enough to print human-sized statues. Dogs, cats, and some great apes may be possible, too.