Way before you kids had touch screens and mice, we had to walk uphill both ways to tell a computer where we were pointing at on the screen. I speak, of course, of light pens. When these photodiodes in a pen were pointed at a CRT, the display driver would tell the computer where the pen was pointing. It’s a pretty incredible video hack today, and these things were around in the 1970s. You could, of course, use a light pen with most of the old 8-bit home computers, including the Commodore 64.

[Jan] has a soft spot for the light pen on the C64. So much so he made a new input device using this tech. It’s great, and if this existed in 1985, all the cool kids would have known about it.

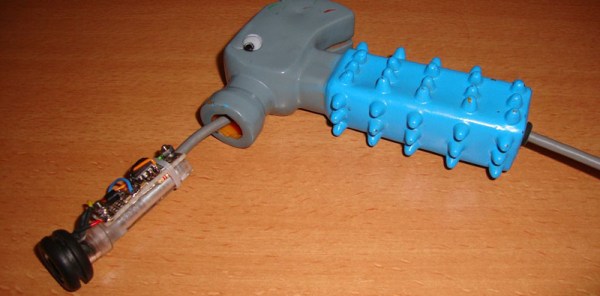

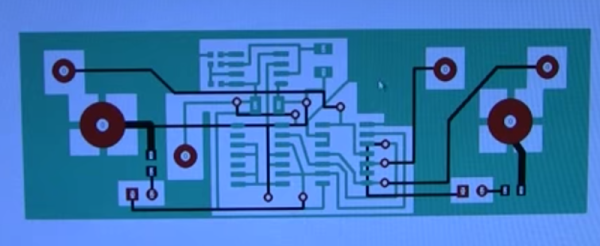

The build is called the LightHammer. It’s a light pen, inside the head of a plastic hammer, with a few springs, nuts, and washers to tell the computer to read the light pen input. The light pen itself is just a photodiode with a few transistors; it was a simple circuit in the 80s, and it’s a simple circuit today.

A new input device isn’t worth anything without an app to show off the tech, and [Jan] is about three steps ahead of us here. He wrote a game for this LightHammer – a digital version of Whac-A-Mole and Simon. They’re exactly what you think they are: the classic ‘repeat the computer’ and ‘murder rodents’ games.

If that’s not enough, [Jan] also built an arcade cabinet for his C64 setup, with the monitor, joysticks, a 1541, and a TV mounted in a cabinet that would look great in a bar. You can check out a video of that and the games using the LightHammer below.

Continue reading “A Revolutionary Input Device, 30 Years Too Late”