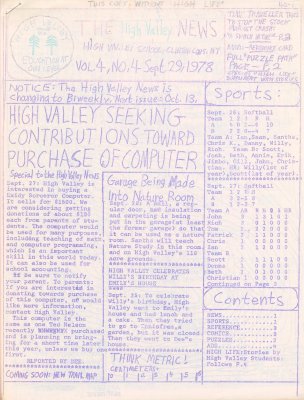

In the 1982 movie Fast Times At Ridgemont High, a classroom of students receives a set of paperwork to pass backward. Nearly every student in the room takes a big whiff of their sheet before setting it down. If you know, you know, I guess, but if you don’t, keep reading.

Those often purple-inked papers were fresh from the ditto machine, or spirit duplicator. Legend has it that not only did they smell good when they were still wet, inhaling the volatile organic compounds within would make the sniffer just a little bit lightheaded. But the spirit duplicator didn’t use ghosts, it used either methanol (wood alcohol), isopropyl, or, if you were loaded, ethyl alcohol.

Invented in 1923 by Wilhelm Ritzerfeld, ditto machines were popular among schools, churches, and clubs for making copies of worksheets, fliers, and so on before the modern copy machine became widespread in the 1980s. Other early duplicating machines include the mimeograph, the hectograph, and the cyclostyle.