Despite the technology itself being widely available and relatively cheap, devices that offer wireless charging as a feature still aren’t as common as many would like. Sure it can’t deliver as much power as something like USB-C, but for low-draw devices that don’t necessarily need to be recharged in a hurry, the convenience is undeniable.

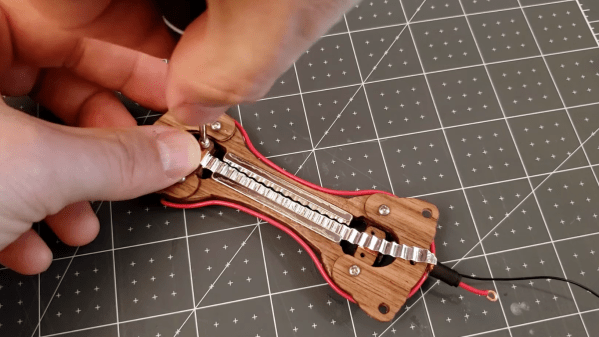

Sick of having to plug it in after each session, [Taylor Burley] decided to take matters into his own hands and add wireless charging capability to his Turtle Beach Recon 200 headset. But ultimately, there’s nothing about this project that couldn’t be adapted to your own particular headset of choice. Or any other device that charges via USB, for that matter.

To keep things simple, [Taylor] used an off-the-shelf wireless charging transmitter and receiver pair. The transmitter is housed in a 3D printed mount that the headset hangs from, and the receiver was simply glued to the top of the headset. The receiver is covered with a thin 3D printed plate, but a couple turns of electrical tape would work just as well if you didn’t want to design a whole new part.

To keep things simple, [Taylor] used an off-the-shelf wireless charging transmitter and receiver pair. The transmitter is housed in a 3D printed mount that the headset hangs from, and the receiver was simply glued to the top of the headset. The receiver is covered with a thin 3D printed plate, but a couple turns of electrical tape would work just as well if you didn’t want to design a whole new part.

Once everything was in place, he then ran a wire down the side of the headset and tapped into the five volt trace coming from the USB port. So now long as [Taylor] remembers to hang the headset up after he’s done playing, the battery will always be topped off the next time he reaches for it.

Considering how many projects we’ve seen that add wireless charging to consumer devices, it’s honestly kind of surprising that it’s still not a standard feature in 2021. Until manufacturers figure out what they want to do with the technology, it seems like hackers will just have to keep doing it themselves.

Continue reading “Gaming Headset Gets Simple Wireless Charging”

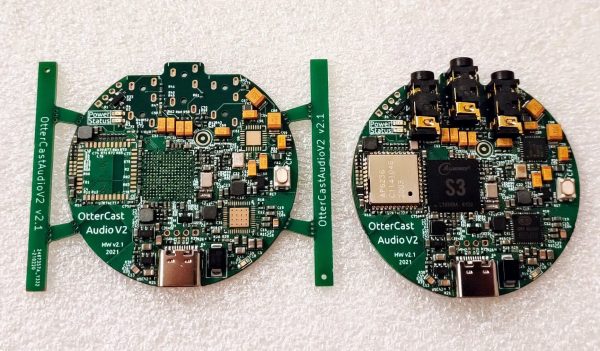

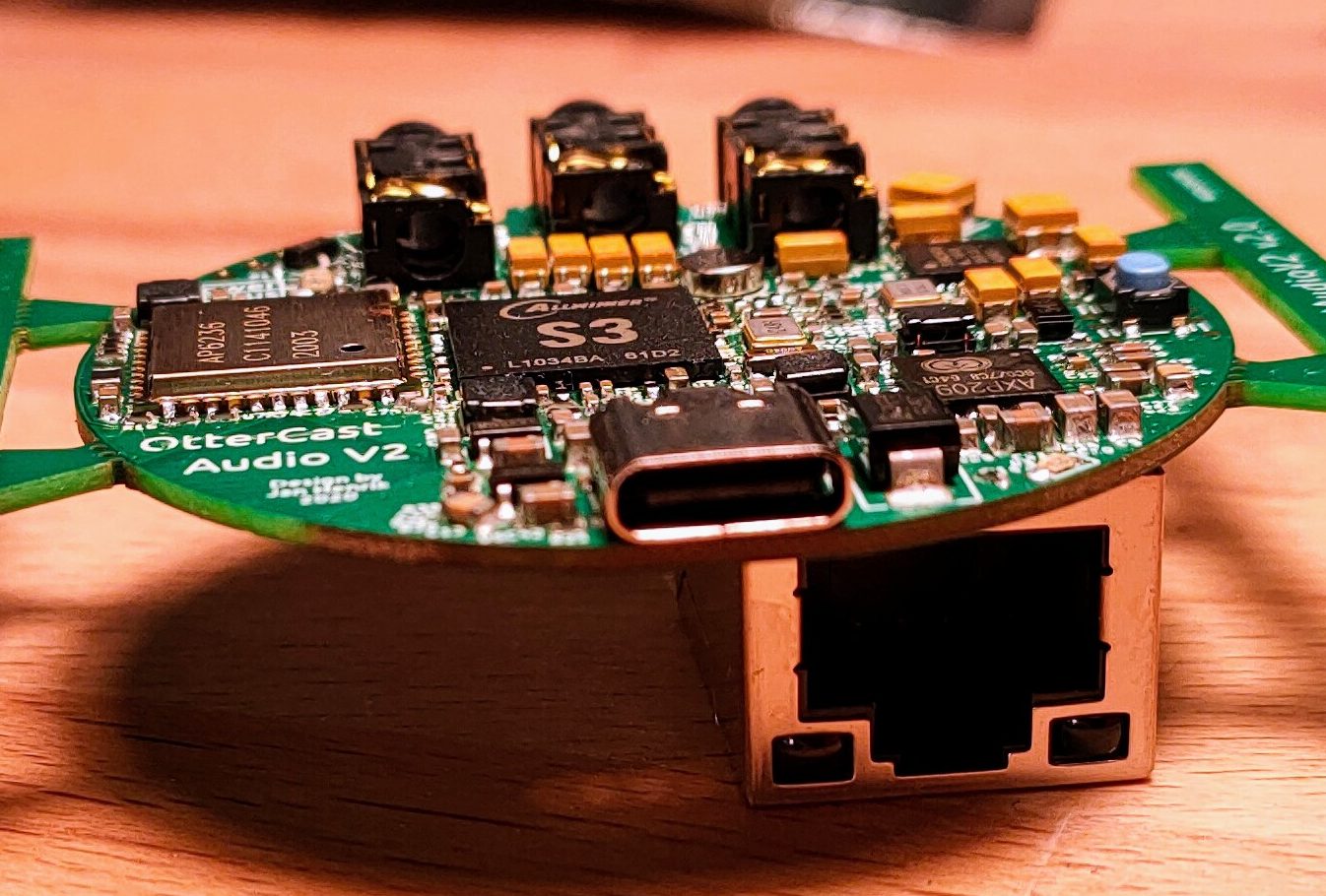

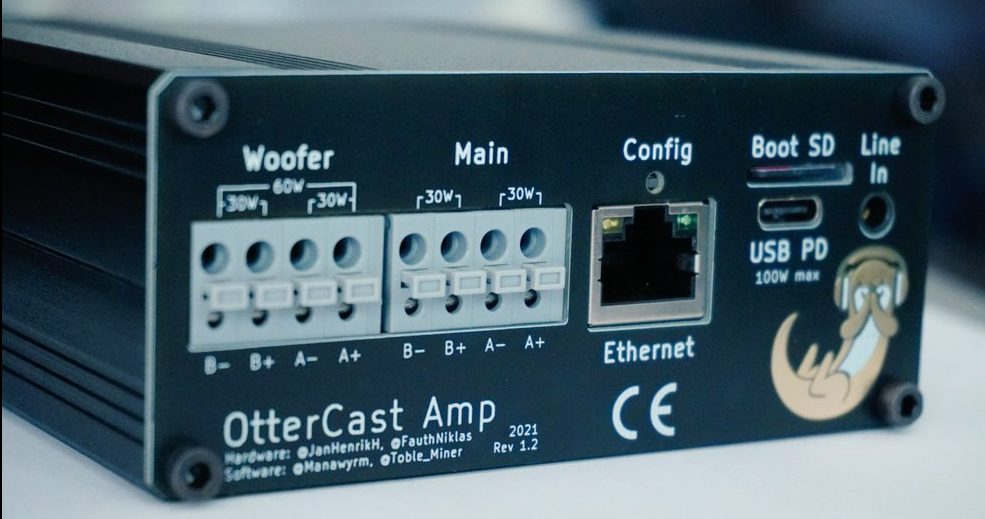

One look at the chassis and it’s clear that unlike the OtterCastAudio this is not a simple Chromecast Audio replacement. The face of the OtterCastAmp is graced by a luscious 340×800 LCD for all the cover art your listening ear can enjoy. And the raft of connectors in the back (and mountain of inductors on the PCBA) make it clear that this is a fully fledged class D amplifier, driving up to 120W of power across four channels. Though it may drive a theoretical 30W or 60W peak across its various outputs, with a maximum supply power of 100W (via USB-C power delivery, naturally) the true maximum output will be a little lower. Rounding out the feature set is an Ethernet jack and some wonderfully designed copper PCB otters to enjoy inside and out.

One look at the chassis and it’s clear that unlike the OtterCastAudio this is not a simple Chromecast Audio replacement. The face of the OtterCastAmp is graced by a luscious 340×800 LCD for all the cover art your listening ear can enjoy. And the raft of connectors in the back (and mountain of inductors on the PCBA) make it clear that this is a fully fledged class D amplifier, driving up to 120W of power across four channels. Though it may drive a theoretical 30W or 60W peak across its various outputs, with a maximum supply power of 100W (via USB-C power delivery, naturally) the true maximum output will be a little lower. Rounding out the feature set is an Ethernet jack and some wonderfully designed copper PCB otters to enjoy inside and out.