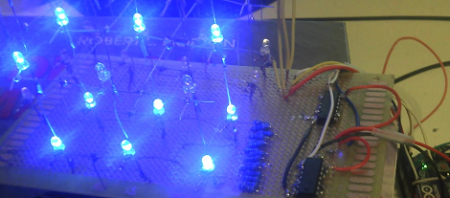

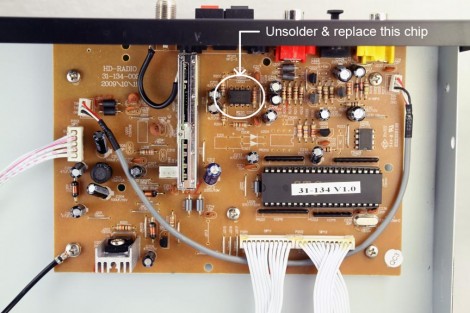

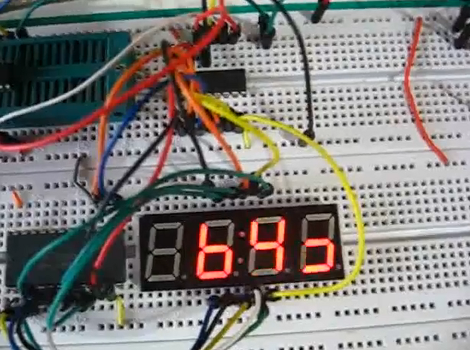

[Jim] just finished restoring an old Seeburg USC1 jukebox for his father using an Arduino, replacing an electromechanical rats nest of wires. The stack of 45 records were replaced with an Arduino Mega 2560 with an Sparkfun MP3 player shield, and he jukebox lights are now controlled with 74595 shift registers. Because his jukebox isn’t taking in money, the dollar bill validator has been modified into a ‘skip song’ button, and when there are no songs in the jukebox queue, there are 500 additional songs on the SD card that will randomly play.

We’ve seen one of [Jim]’s builds before. Earlier this year he repaired a thirty year old Pachinko machine using the same Arduino + MP3 shield setup. It looks like [Jim] is pretty skilled at revitalizing bulky old electronics. The jukebox restoration is great and has a lot more class than the internet-connected touch screen monstrosities that we still pump money into.

Check out the video after the break for a walk through of this restoration.