People have been coming up with clever ways to bring light to the darkness since we lived in caves, so it’s no surprise we still love finding interesting ways to illuminate our world. [Michael] designed a simple, but beautiful, book lamp that’s easy to assemble yourself.

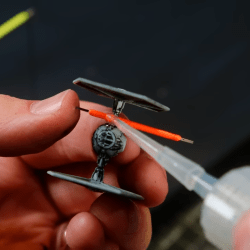

This build really outshines its origins as an assembly of conductive tape, paper, resistors, LEDs, button cells, and a binder clip. With a printable template for the circuit, this project seems perfect for a makerspace workshop or school science project kids could take home with them. [Michael] walks us through assembling the project in a quick video and even has additional information available for working with conductive tape which makes it super approachable for the beginner.

The slider switch is particularly interesting as it allows you to only turn on the light when the book is open using just conductive tape and paper. We can think of a few other ways you could control this, but they quickly start increasing the part count which makes this particularly elegant. By changing the paper used for the shade or the cover material for the book, you can put a fun spin on the project to match any aesthetic.

If you want to build something a little more complex to light your world, how about a 3D printed Shoji lamp, a color-accurate therapy lamp, or a lamp that can tell you to get back to work.

Continue reading “DIY Book Lamp Is A Different Take On The Illuminated Manuscript”