You’ve seen CMOS logic, you’ve seen diode-resistor logic, you’ve seen logic based on relays, and some of you who can actually read have heard about rod logic. [Julian] has just invented optoisolator logic. He has proposed two reasons why this hasn’t been done before: either [Julian] is exceedingly clever, or optoisolator logic is a very stupid idea. It might just be the former.

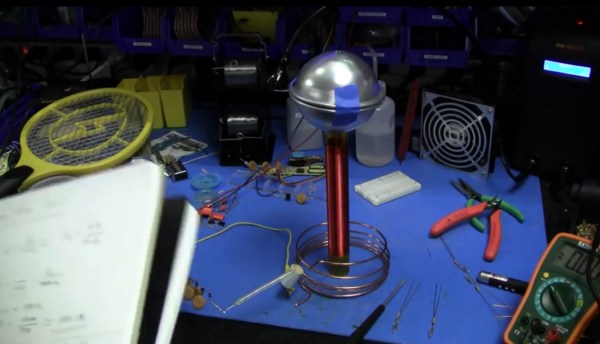

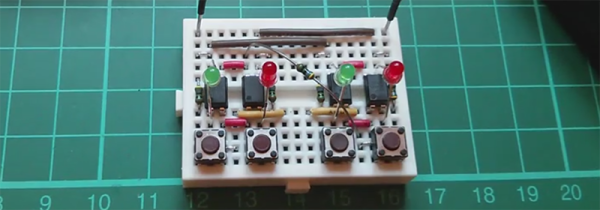

Inside each optoisolator is a LED and a phototransistor. There’s no electrical connection between the two devices, which is exactly what you need in something that’s called an isolator. [Julian] was playing around with some optoisolators one day to create a weird push-pull circuit; the emitter of one phototransistor was connected to the collector of another. Tying the other ends of the phototransistor to +5V and Gnd meant he could switch between VCC and VDD, with every other part of the circuit isolated. This idea whirled around his mind for a few months until he got the idea of connecting even more LEDs to the inputs of the optoisolators. He could then connect the inputs of the isolators to +5V and Gnd because of the voltage drop of four LEDs.

A few more wheels turned in [Julian]’s head, and he decided to connect a switch between the two optoisolators. Connecting the ‘input’ of the circuit to ground made the LED connected to +5V light up. Connecting the input of the circuit to +5 made the LED connected to ground light up. And deeper down the rabbit hole goes [Julian].

With a few more buttons and LEDs, [Julian] created something that is either an AND, NAND, OR NOR, depending on your point of view. He already has an inverter and a few dozen more optoisolators coming from China.

It is theoretically possible to build something that could be called a computer with this, but that would do the unique properties of this circuit a disservice. In addition to a basic “1” and “0” logic state, these gates can also be configured for a tri-state input and output. This is huge; there are only two universal gates when you’re only dealing with 1s and 0s. There are about 20 universal logic gates if you can deal with a two.

It’s not a ternary computer yet (although we have seen those), but it is very cool and most probably not stupid.

Video below.

A high school

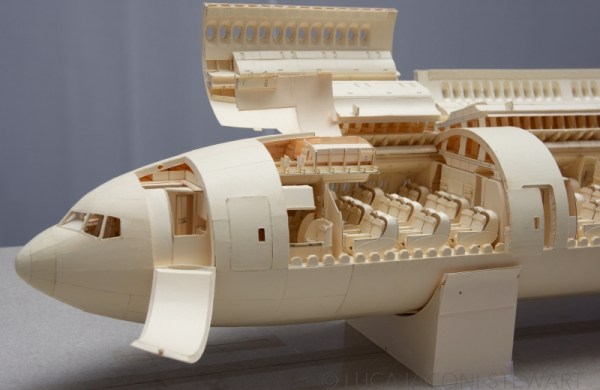

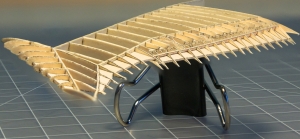

A high school  The design is manually drawn in Illustrator from the schematics, then is printed directly onto the manilla folders. Wielding an X-acto knife like a watch-maker, [Luca] cuts all the segments out and places them with whispers of glue. Pistons. Axles. Clamps. Tie rods. Brackets. Even pneumatic hoses – fractions of a toothpick thin – are run to their proper locations. A mesh behind the engine was latticed manually from of hundreds of strands. If that was not enough, it all moves and works exactly as it does on the real thing.

The design is manually drawn in Illustrator from the schematics, then is printed directly onto the manilla folders. Wielding an X-acto knife like a watch-maker, [Luca] cuts all the segments out and places them with whispers of glue. Pistons. Axles. Clamps. Tie rods. Brackets. Even pneumatic hoses – fractions of a toothpick thin – are run to their proper locations. A mesh behind the engine was latticed manually from of hundreds of strands. If that was not enough, it all moves and works exactly as it does on the real thing.