Communicating with a satellite seems like something that should take a lot of equipment. A fancy antenna and racks full of receivers, filters, and amplifiers would seem to be the entry-level suite of gear. But listening to a weather satellite with an old pair of rabbit ears and an SDR dongle? That’s a thing too.

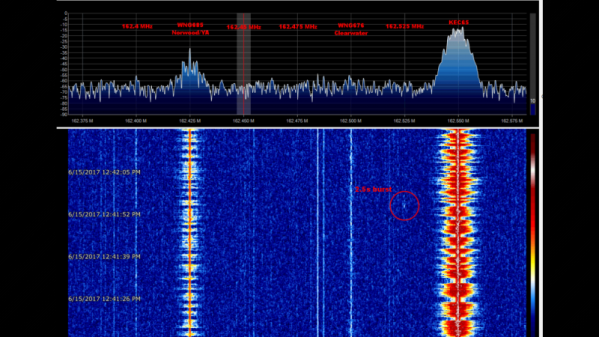

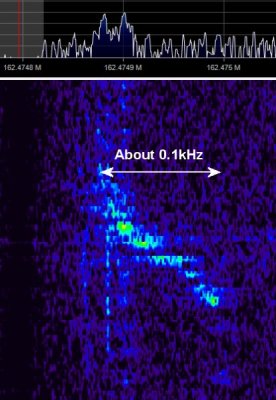

There was a time when a pair of rabbit ears accompanied every new TV. Those days are gone, but [Thomas Cholakov (N1SPY)] managed to find one of the old TV dipoles in his garage, complete with 300-ohm twinlead and spade connectors. He put it to work listening to a NOAA weather satellite on 137 MHz by configuring it in a horizontal V-dipole arrangement. The antenna legs are spread about 120° apart and adjusted to about 20.5 inches (52 cm) length each. The length makes the antenna resonant at the right frequency, the vee shape makes the radiation pattern nearly circular, and the horizontal polarization excludes signals from the nearby FM broadcast band and directs the pattern skyward. [Thomas] doesn’t mention how he matched the antenna’s impedance to the SDR, but there appears to be some sort of balun in the video below. The satellite signal is decoded and displayed in real time with surprisingly good results.

Itching to listen to satellites but don’t have any rabbit ears? No problem — just go find a cooking pot and get to it.

Continue reading “Old Rabbit Ears Optimized For Weather Satellite Downlink”