We’re guessing most readers can cite things from their youth which gave them an interest in technology, and spurred on something which became a career or had a profound impact on their life. Public engagement activities for technology or science have a crucial role in bringing forth the next generations of curious people into those fields, and along the way they can provide some fun for grown-ups too.

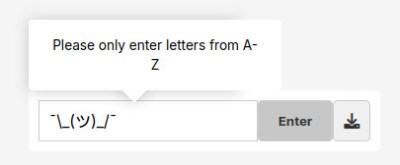

A case in point is from NASA’s Landsat engagement team, Your Name In Landsat. Type in a text string, and it will spell it out in Earth features seen by the imaging satellites, that resemble letters. Endless fun can be had by all, as the random geology flashes by.

In itself, though fun, it’s not quite a hack. But behind the kids toy we’re curious as to how the images were identified, and mildly sad that the NASA PR people haven’t seen fit to tell us. We’re guessing that over the many decades of earth images there exists a significant knowledge base of Earth features with meaningful or just amusing shapes that will have been gathered by fun-loving engineers, and it’s possible that this is what informed this feature. But we’d also be curious to know whether they used an image classification algorithm instead. There must be a NASA employee or two who reads Hackaday and could ask around — let us know in the comments.

Meanwhile, if LANDSAT interests you, it’s possible to pull out of the air for free.