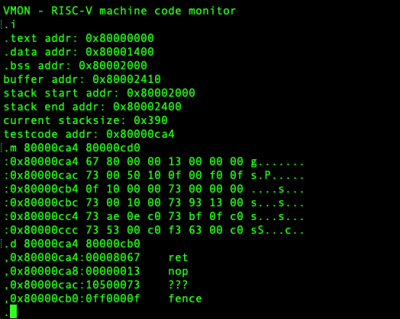

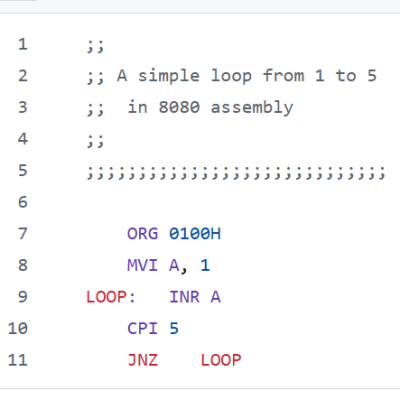

Have you ever dreamed of making a bash script that assembles Intel 8080 machine code? [Chris Smith] did exactly that when he created xa.sh, a cross-assembler written entirely in Bourne shell script.

The script exists in part as a celebration of the power inherent in a standard Unix shell with quite ordinary POSIX-compliant command line tools like awk, sed, and printf. But [Chris] admits that mostly he found the whole project amusing.

It’s designed in a way that adding support for 6502 and 6809 machine code would be easy, assuming 8080 support isn’t already funny enough on its own.

It’s not particularly efficient and it’s got some quirks, most of which involve syntax handling (hexadecimal notation should stick to 0 or 0x prefixes instead of $ to avoid shell misinterpretations) but it works.

Want to give it a try? It’s a shell script, so pull a copy and and just make it executable. As long as the usual command-line tools exist (meaning your system is from sometime in the last thirty-odd years), it should run just fine as-is.

An ambitious bash script like this one recalls how our own Al Williams shared ways to make better bash scripts by treating it just a bit more like the full-blown programming language it qualifies as.