There may be no place on Earth less visited by humans than the South Pole. Despite a permanent research base with buildings clustered about the pole and active scientific programs, comparatively few people have made the arduous journey there. From October to February, up to 200 people may be stationed at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station for the Antarctic summer, and tourists checking an item off their bucket lists come and go. But by March, when the sun dips below the horizon for the next six months, almost everyone has cleared out, except for a couple of dozen “winter-overs” who settle in to maintain the station, carry on research, and survive the worst weather Mother Nature brews up anywhere on the planet.

To be a winter-over means accepting the fact that whatever happens, once that last plane leaves, you’re on your own for eight months. Such isolation and self-reliance require special people, and Dr. Jerri Nielsen was one who took the challenge. But as she and the other winter-overs watched the last plane leave the Pole in 1998 and prepared for the ritual first-night screening of John Carpenter’s The Thing, she had no way of knowing what she would have to do to survive the cancer that was even then growing inside her.

Continue reading “Jerri Nielsen: Surviving The Last Place On Earth”

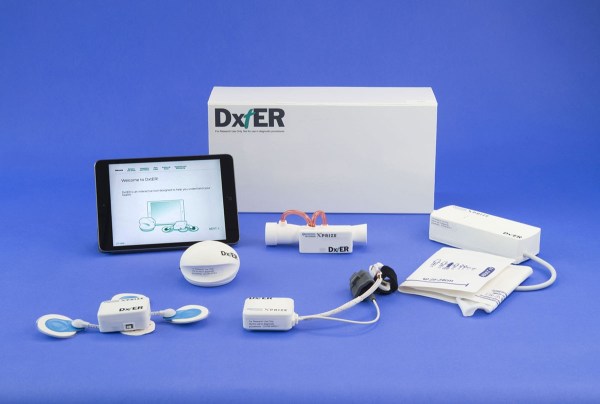

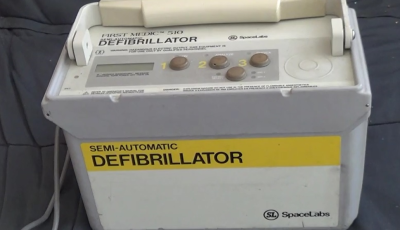

It’s safe to say we’ve all seen engineering solve part of this problem already. Over the last decade, Automatic External Defibrillators have become ubiquitous. The life-saving hardware is designed to be used by non-doctors to save someone whose heart rhythms have become irregular. [Chris Nefcy] helped develop AEDs and

It’s safe to say we’ve all seen engineering solve part of this problem already. Over the last decade, Automatic External Defibrillators have become ubiquitous. The life-saving hardware is designed to be used by non-doctors to save someone whose heart rhythms have become irregular. [Chris Nefcy] helped develop AEDs and