In honor of our recently announced 2022 Cyberdeck Contest, we decided to do things a little differently for this week’s Hack Chat. Rather than pick just one host, we looked back through the archive and selected some of the most impressive builds we’ve seen and asked their creators if they’d like to take part in a freewheeling discussion about their creations and the nascent community surrounding these bespoke computing devices.

Despite conflicting time zones and at least one international vacation, we were able to put together an impressive panel to helm this special Cyberdeck Brainstorming Hack Chat:

- [bootdsc] – Creator of the VirtuScope, and founder of the Cyberdeck Cafe

- [Back7] – Speaker during the 2021 Remoticon, responsible for the Pelican case craze

- [H3lix] – Moderator of the Cyberdeck Discord server

- [a8ksh4] – Builder of the Chonky Palmtop and Paper Pi Handheld

- [Io Tenino] – Builder of the and the Joopyter retro personal terminal

- [cyzoonic] – Builder of the watertight ruggedized cyberdeck featured in the 2022 Sci-Fi Contest

So what did this accomplished group of cyberdeck builders have to talk about? Well, quite a bit. During a lively conversation, these creators not only swapped stories and details about their own builds, but answered questions from those looking for inspiration and guidance.

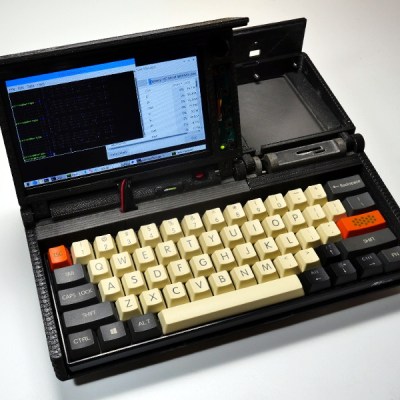

The discussion immediately kicked off with what’s perhaps the most obvious question: why build a cyberdeck if we already have laptops and smartphones — mobile computing form factors which [Io Tenino] admits are likely as close to perfect as we can get with current technology. Most of the builders agreed that a big part of the appeal is artistic, as the design and construction of their personal deck allowed them to show off their creativity.

But what of productivity? Can these custom machines do more than look good on a shelf? There seemed to be consensus that it was difficult to compete with a standard laptop in terms of general purpose computing, but that a cyberdeck tailored to a specific use case could be a powerful tool.

For example, [bootdsc] built a high-power WiFi adapter as well as an RTL-SDR receiver and up-converter into the VirtuScope, while [Io Tenino] says the Joopyter’s integrated printer is occasionally used to run off a grocery list. [H3lix] also mentioned that the trend towards ever-thinner laptops has meant removing ports and expansion options which used to be taken for granted, a potentially frustrating situation for hardware hackers that a cyberdeck can alleviate.

Naturally, the Chat also covered more technical aspects of cyberdeck design. There was quite a bit of discussion about powering these custom machines, and whether or not internal batteries were even a necessary design consideration. In keeping with the survivalist theme, [cyzoonic] included 18650 cells and an integrated charger, while [Io Tenino] is content to use a standard USB battery bank. Ultimately, like most aspects of an individual’s cyberdeck, the answer largely depended on what the user personally wished to accomplish.

Others wondered if the protection provided by these cases was really necessary given the relatively easy life most of these machines will lead, especially given their considerable cost. Although to that end, we also saw some suggestions for alternative cases which provide a similar look and feel at a more hacker-friendly price point.

Though they are certainly popular, Pelican cases are just one option when planning your own build. Many chose to 3D print their own enclosures, and there’s even the argument to be made that the rise of desktop 3D printing has helped make cyberdeck construction more practical than it has been in the past. Others prefer to use the chassis of an old computer or other piece of consumer electronics as a backbone for their deck, which fits well with the cyberpunk piecemeal aesthetic. That said, the Chat seemed in agreement that care needed to be taken so as not to destroy a rare or valuable piece of vintage hardware in the process.

This Hack Chat was a great chance to get some behind the scenes info about these fantastic builds, but even if you didn’t have a specific question, it was an inspiring discussion to say the least. We’re willing to bet that the design for some of the cyberdecks that get entered into the contest will have been shaped, at least in part, due to this unique exchange of niche ideas and information. Special thanks to [bootdsc], [Back7], [H3lix], [a8ksh4], [Io Tenino], and [cyzoonic] for taking the time to share this glimpse into their fascinating community with us.

The Hack Chat is a weekly online chat session hosted by leading experts from all corners of the hardware hacking universe. It’s a great way for hackers connect in a fun and informal way, but if you can’t make it live, these overview posts as well as the transcripts posted to Hackaday.io make sure you don’t miss out.