Computer graphics have come a long way. Some video games today exceed what would have passed for stunning cinema animation only a few years ago. However, it hasn’t always been like this. One of the earliest forms of computer-generated graphics used text characters to draw on printers.

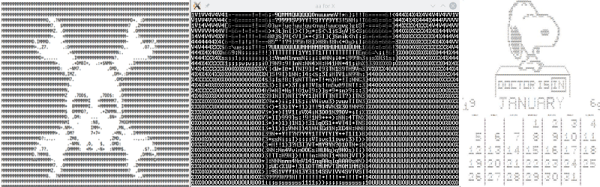

Early computer rooms were likely to have a Snoopy character on green and white fan-fold paper. Calendars with some artwork were also popular (see left, and find out about the FORTRAN that created it, if you like). Ham radio operators who use teletypes (RTTY, in ham parlance) often had vast collections of punched tape that held artwork. Given that most hams in the 1950s and 1960s were men and the times were different, a lot of them were more or less “R” rated.

Early computer rooms were likely to have a Snoopy character on green and white fan-fold paper. Calendars with some artwork were also popular (see left, and find out about the FORTRAN that created it, if you like). Ham radio operators who use teletypes (RTTY, in ham parlance) often had vast collections of punched tape that held artwork. Given that most hams in the 1950s and 1960s were men and the times were different, a lot of them were more or less “R” rated.

Not all of them were, though. For example, Richard Nixon was decidedly “G” rated (see right). Simple pictures would use single characters, but sophisticated ones would use the backspace character to overprint multiple characters.

Not all of them were, though. For example, Richard Nixon was decidedly “G” rated (see right). Simple pictures would use single characters, but sophisticated ones would use the backspace character to overprint multiple characters.

Ham Radio Art

You often hear this described as ASCII art, today, although hams usually use 5-bit BAUDOT code, so that’s a misnomer for those images, at least. Of course, today, people aren’t keen on storing roll after roll of paper tape (or even owning a tape reader) so there have been several projects to capture this art in a more modern format.

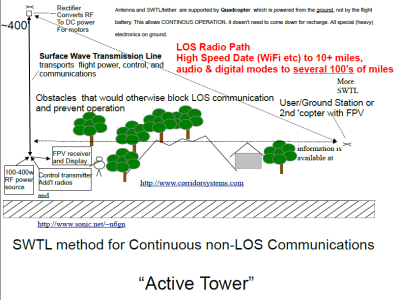

Although there is still some RTTY art activity, picture sending has been mostly replaced by slow scan TV (SSTV) which sends actual still images or other modes like FAX. Some of the newer digital modes even have the ability to send pictures. You can be discussing your radio for example, and then show the other ham a photo of the radio.

Continue reading “Retrotechtacular: ASCII Art In The 19th Century” →

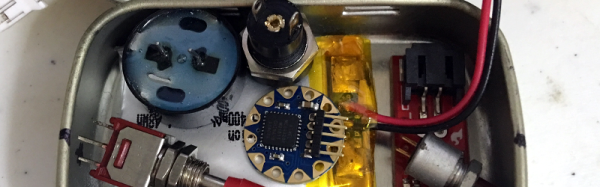

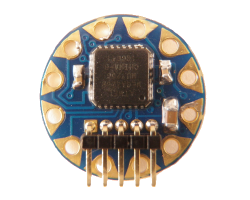

[Rob Bailey] likes to build things and he likes ham radio. We are guessing he likes mints too since he’s been known to jam things into Altoids tins. He had been thinking about building a code practice oscillator in a Altoids Smalls tin, but wasn’t sure he could squeeze an Arduino Pro Mini in there too. Then he found the TinyLily Mini. The rest is history, as they say,

[Rob Bailey] likes to build things and he likes ham radio. We are guessing he likes mints too since he’s been known to jam things into Altoids tins. He had been thinking about building a code practice oscillator in a Altoids Smalls tin, but wasn’t sure he could squeeze an Arduino Pro Mini in there too. Then he found the TinyLily Mini. The rest is history, as they say,