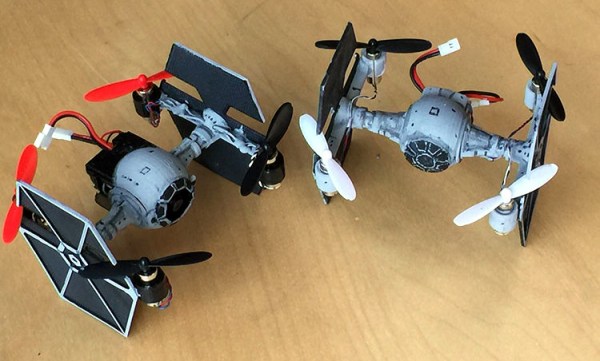

These are things of beauty, and when in flight, the Tie Fighter Quadcopters look even better because the spinning blades become nearly transparent. Most of the Star Wars-themed quadcopter hacks we’ve seen are complicated builds that we know you’re not even going to try. But [Cuddle Burrito’s] creations are for every hacker in so many different ways.

First off, he’s starting with very small commodity quadcopters that are cheap (and legal) for anyone to own and fly. Both are variations of the Hubsan X4; the H107C and the H107L. The stock arms of these quadcopters extend from the center of the chassis, but that needs to change for TFFF (Tie Fighter Form Factor). The solution is of course 3D Printing. The designs have been published for both models and should be rather simple to print.

First off, he’s starting with very small commodity quadcopters that are cheap (and legal) for anyone to own and fly. Both are variations of the Hubsan X4; the H107C and the H107L. The stock arms of these quadcopters extend from the center of the chassis, but that needs to change for TFFF (Tie Fighter Form Factor). The solution is of course 3D Printing. The designs have been published for both models and should be rather simple to print.

ABS is used as the print medium, which makes assembly easy using a slurry of acetone and ABS to weld the seams together. Motor wires need to be extended and routed through the printed arms, but otherwise you don’t need anything else. Even the original screws are reused in this design. Check out test flights in the video after the break As for the more custom builds we mentioned, there’s the Drone-enium Falcon.