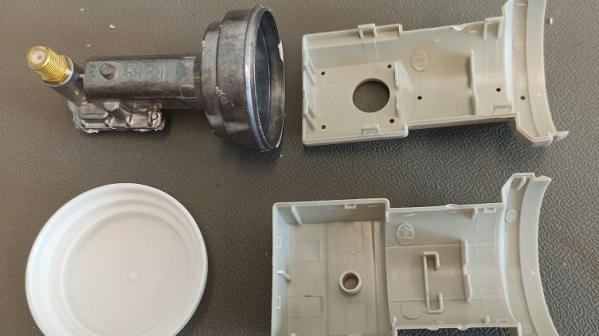

A word of advice: If you see an old direct satellite TV dish put out to the curb, grab it before the trash collector does. Like microwave ovens, satellite dishes are an e-waste wonderland, and just throwing them away before taking out the good stuff would be a shame. And with dishes, the good stuff basically amounts to the bit at the end of the arm that contains the feedhorn and low-noise block downconverter (LNB).

But what does one do with such a thing once it’s harvested? Lots of stuff, including modifying it for use with the QO-100 geosynchronous satellite (German link). That’s what [Sebastian Westerhold] and [Celin Matlinski] did with a commodity LNB, although it seems more like something scored on the cheap from one of the usual sources rather than picking through trash. Either way, these LNBs are highly integrated devices that at built specifically for satellite TV use, but with just a little persuasion can be nudged into the K-band to receive the downlink signals from hams using QO-100 as a repeater.

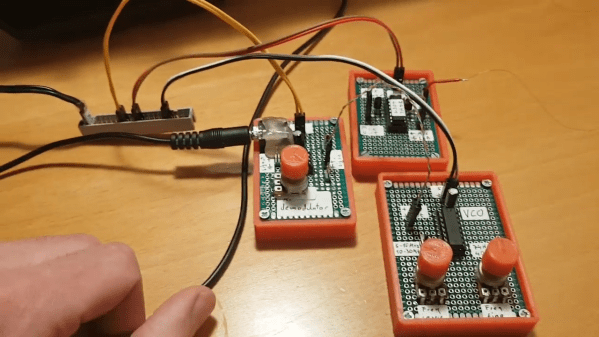

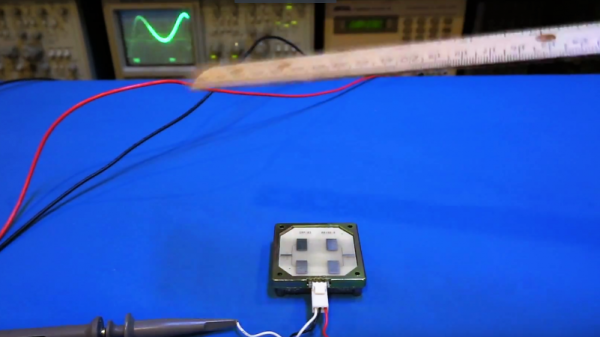

The mods are simple — snipping out the 25 MHz reference crystal on the LNB board and replacing it with a simple LC bandpass filter. This allows the local oscillator on the LNB to be referenced to an external signal generator; when fed with a 25.78 MHz signal, it’s enough to goose the LNB up to 10,490 MHz — right about the downlink frequency. [Sebastian] and [Celin] tested the mods and found that it was easily able to detect the third harmonics of a 3.5-ish GHz signal.

As for testing on actual downlink signals from the satellite, that’ll have to wait. For now, if you’re interested in satellite comms, and you live on the third of the planet covered by QO-100, keep an eye out for those e-waste LNBs and get to work.