While most of us won’t ever play Wimbledon, we can play Pong. But it isn’t the same without the thrill of the sportscaster’s commentary during the game. Thanks to [Parth Parikh] and an LLM, you can now watch Pong matches with commentary during the game. You can see the very cool result in the video below — the game itself starts around the 2:50 mark. Sadly, you don’t get to play. It seems like it wouldn’t be that hard to wire yourself in with a little programming.

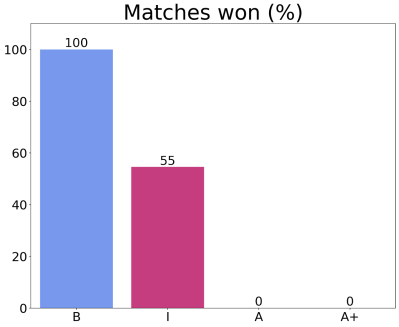

The game features multiple AI players and two announcers. There are 15 years of tournaments, including four majors, for a total of 60 events. In the 16th year, the two top players face off in the World Championship Final.

There are several interesting techniques here. For one, each action is logged as an event that generates metrics and is prioritized. If an important game event occurs, commentary pauses to announce that event and then picks back up where it left off.

We really want to see a one- or two-player human version of this. Please tell us if you take on that challenge. Even if you don’t write it, maybe the AI can write it for you.

Continue reading “AI Brings Play-by-Play Commentary To Pong”