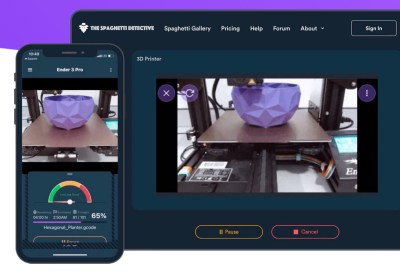

For readers that might not spend their free time watching spools of PLA slowly unwind, The Spaghetti Detective (TSD) is an open source project that aims to use computer vision and machine learning to identify when a 3D print has failed and resulted in a pile of plastic “spaghetti” on the build plate. Once users have installed the OctoPrint plugin, they need to point it to either a self-hosted server that’s running on a relatively powerful machine, or TSD’s paid cloud service that handles all the AI heavy lifting for a monthly fee.

Unfortunately, 73 of those cloud customers ended up getting a bit more than they bargained for when a configuration flub allowed strangers to take control of their printers. In a frank blog post, TSD founder Kenneth Jiang owns up to the August 19th mistake and explains exactly what happened, who was impacted, and how changes to the server-side code should prevent similar issues going forward.

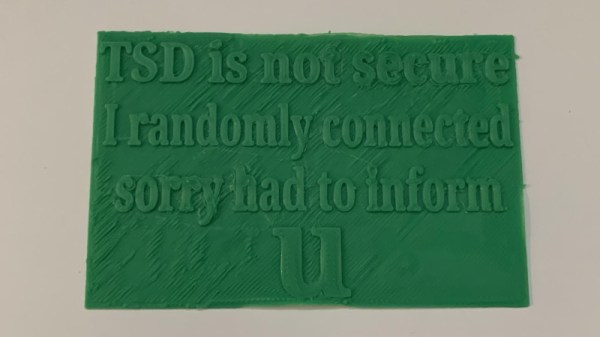

For the record, it appears no permanent damage was done, and everyone who was potentially impacted by this issue has been notified. There was a fairly narrow window of opportunity for anyone to stumble upon the issue in the first place, meaning any bad actors would have had to be particularly quick on their keyboards to come up with some nefarious plot to sabotage any printers connected to TSD. That said, one user took to Reddit to show off the physical warning their printer spit out; the apparent handiwork of a fellow customer that discovered the glitch on their own.

According to Jiang, the issue stemmed from how TSD associates printers and users. When the server sees multiple connections coming from the same public IP, it’s assumed they’re physically connected to the same local network. This allows the server to link the OctoPrint plugin running on a Raspberry Pi to the user’s phone or computer. But on the night in question, an incorrectly configured load-balancing system stopped passing the source IP addresses to the server. This made TSD believe all of the printers and users who connected during this time period were on the same LAN, allowing anyone to connect with whatever machine they wished.

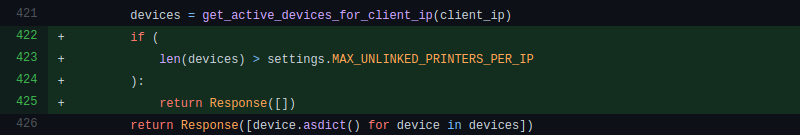

The mix-up only lasted about six hours, and so far, only the one user has actually reported their printer being remotely controlled by an outside party. After fixing the load-balancing configuration, the team also pushed an update to the TSD code which puts a cap on how many printers the server will associate with a given IP address. This seems like a reasonable enough precaution, though it’s not immediately obvious how this change would impact users who wish to add multiple printers to their account at the same time, such as in the case of a print farm.

While no doubt an embarrassing misstep for the team at The Spaghetti Detective, we can at least appreciate how swiftly they dealt with the issue and their transparency in bringing the flaw to light. This is also an excellent example of how open source allows the community to independently evaluate the fixes applied by the developer in response to a discovered flaw. Jiang says the team will be launching a full security audit of their own as well, so expect more changes getting pushed to the repository in the near future.

We were impressed with TSD when we first covered it back in 2019, and glad to see the project has flourished since we last checked in. Trust is difficult to gain and easy to lose, but we hope the team’s handling of this issue shows they’re on top of things and willing to do right by their community even if it means getting some egg on their face from time to time.