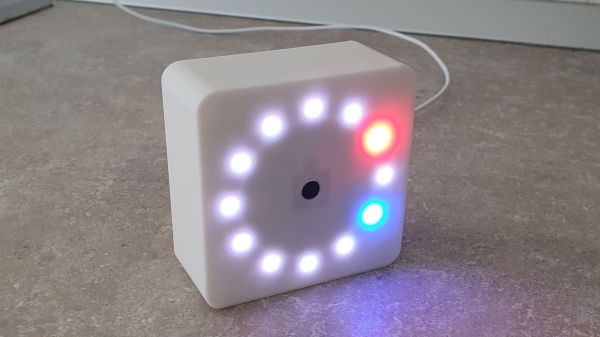

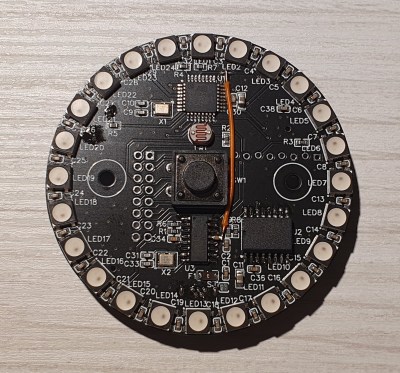

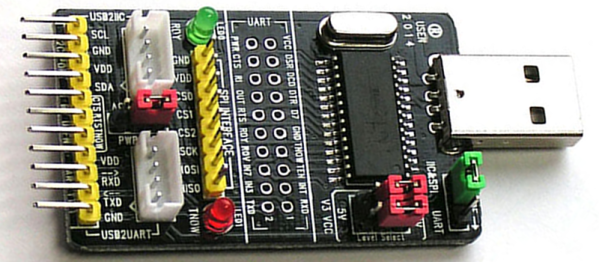

Perhaps without many of us realising it, our single board computers perform the task of making programming their processor or SoC a lot easier. They take care of setting the right lines or commands to put the chip in programming mode, they deal with timings, such that we simply fire our code from our dev environment without having to expend much thought. It’s not as though it’s difficult to program most microcontrollers, but there is usually a procedure to set the chip in programming mode. Tired of pressing buttons to achieve this with the ESP32, [DoganM95] took the time to create an all-in-one USB ESP32 programming board.

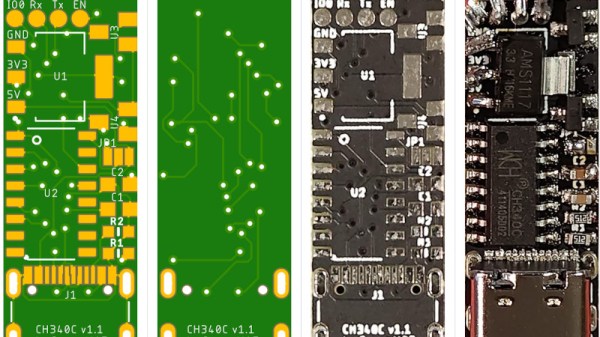

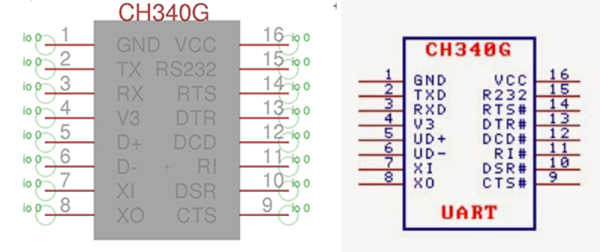

It’s a straightforward enough CH340C design that also has a USBC-PD chip on-board allowing powering of an attached ESP32 from PD sources. It’s all the stuff you’d find incorporated on a little dev board, without the ESP32, so while it’s nothing earth-shattering it’s also a neat and useful little addition to your arsenal. Unsurprisingly it’s not the first time someone’s created a similar board for a commercially available ESP32 module.