[Ben Krasnow], builder of amazingly complex and technical devices, is finally starting work on his ruby laser. He’s been collecting parts for this project for the past few years, but only recently has he started recreating the first visible light laser.

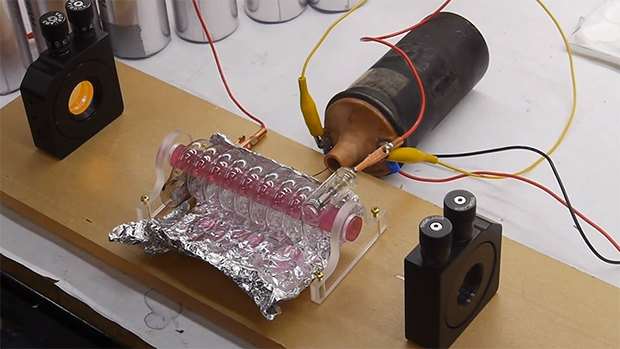

While the design and manufacture of the first ruby laser was astonishingly complex, the basic idea behind it is pretty simple. [Ben]’s laser uses a synthetic ruby rhod with the ends ground optically flat. This rod is placed inside a flash tube. When the flash tube lights up, the rod absorbs the light and re-emits it as a coherent beam for several milliseconds. This beam bounces between two mirrors – one fully reflective and another partially reflective – and emits a constant stream of coherent photons. It’s tremendously more complex than simply connecting a laser diode to a power source, but replicating a build that graced the covers of Time and Newsweek only fifty years ago is pretty impressive

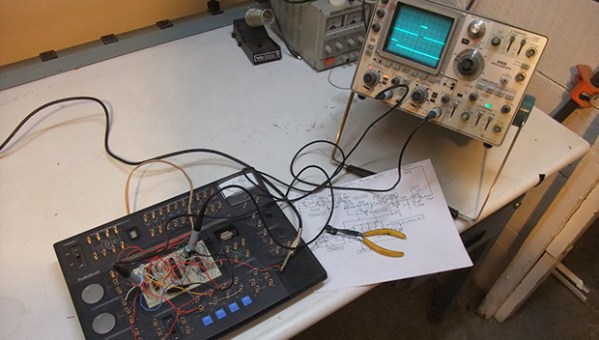

Right now, [Ben] has most of the mechanical and optical parts of his ruby laser on his workbench. The next step is constructing a huge capacitor bank to charge the flash tube every millisecond or so. What [Ben] will end up using his laser for remains up in the air, but if we come across some erbium or neodymium rods we’ll be sure to send them his way.