When you think of supercomputers, visions of big boxes and blinkenlights filling server rooms immediately appear. Since the 90s or thereabouts, these supercomputers have been clusters of computers, all working together on a single problem. For the last twenty years, people have been building their own ‘supercomputers’ in their homes, and now we have cheap ARM single board computers to play with. What does this mean? Personal supercomputers. That’s what [Jason Gullickson] is building for his entry to the Hackaday Prize.

The goal of [Jason]’s project isn’t to break into the Top 500, and it’s doubtful it’ll be more powerful than a sufficiently modern desktop workstation. The goal for this project is to give anyone a system that has the same architecture as a large-scale cluster to facilitate learning about high-performance applications. It also has a front panel covered in LEDs.

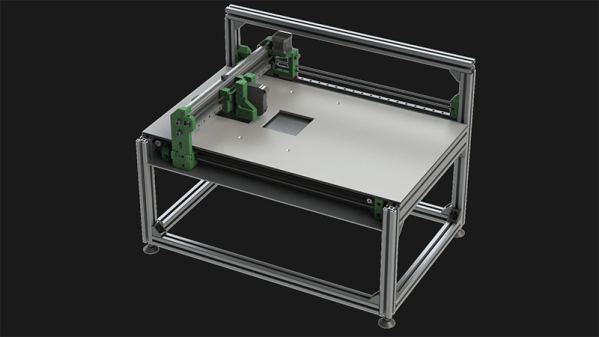

The design of this system is built around a the PINE64 SOPINE module, or basically a 64-bit quad-core CPU stuck onto a board that fits in an SODIMM socket. If that sounds like the Raspberry Pi Computer Module, you get a cookie. Unlike the Pi Compute Module, the people behind the SOPINE have created something called a ‘Clusterboard’, or eight vertical SODIMM sockets tied together with a single controller, power supply, and an Ethernet jack. Yes, it’s a board meant for cluster computing.

To this, [Jason] is adding his own twist on a standard, off-the-shelf breakout board. This Clusterboard is mounted to a beautiful aluminum enclosure, and the front panel is loaded up with a whole bunch of almost vintage-looking red LEDs. These LEDs indicate the current load on each bit of the cluster, providing immediate visual feedback on how those computations are going. With the right art — perhaps something in harvest gold, brown, and avocado — this supercomputer would look like it’s right out of the era of beautiful computers. At any rate, it’s a great entry for the Hackaday Prize.